"Only later did the connection to the local community become more evident, and that’s when they started being called nozes de Cascais. There’s no single point of origin—it’s a confection shaped by centuries of tradition—but at least in Cascais, this sweet took on the form we know today nearly 100 years ago."

Many traditional Portuguese sweets are often linked to old convents, hence the label doces conventuais (convent sweets). But João Pedro Gomes argues that this is a “constructed myth”. He recently collaborated with fellow expert Professor Isabel Drumond Braga to debunk a key manuscript that had long supported this theory—revealing it to be a forgery, created two centuries after the fact.

“There’s no proven case of any sweet in Portugal actually originating from a convent. Techniques were widely shared, and everyone made sweets. It was only in the 19th century that this idea emerged—that nuns made different kinds of confections. It came about as a reaction to the liberal revolution... Society changed, and some people longed for the golden days of Baroque Portugal. This nostalgia led to the romanticised notion that convents preserved a lost culinary heritage. But historically, there’s no evidence for it—Portugal has no verified recipe book originating from any convent. And in the case of nozes de Cascais, there’s nothing to suggest a connection either.”

From the 1960s and 70s onwards, home production likely played a key role in spreading the popularity of nozes. “After the 1974 revolution, Portugal began modernising, and that brought whipped cream, custards, and other novelties—across the country, traditional sweets were somewhat left behind because people were drawn to exciting new trends, like towering strawberry and cream cakes they had never seen before,” explains João Pedro Gomes. “In fact, studies in anthropology suggest that the rise of doces conventuais festivals in Portugal may have been a reaction to this modernisation. Interestingly, these festivals only started appearing in the late 1980s.”

How are Nozes de Cascais made?

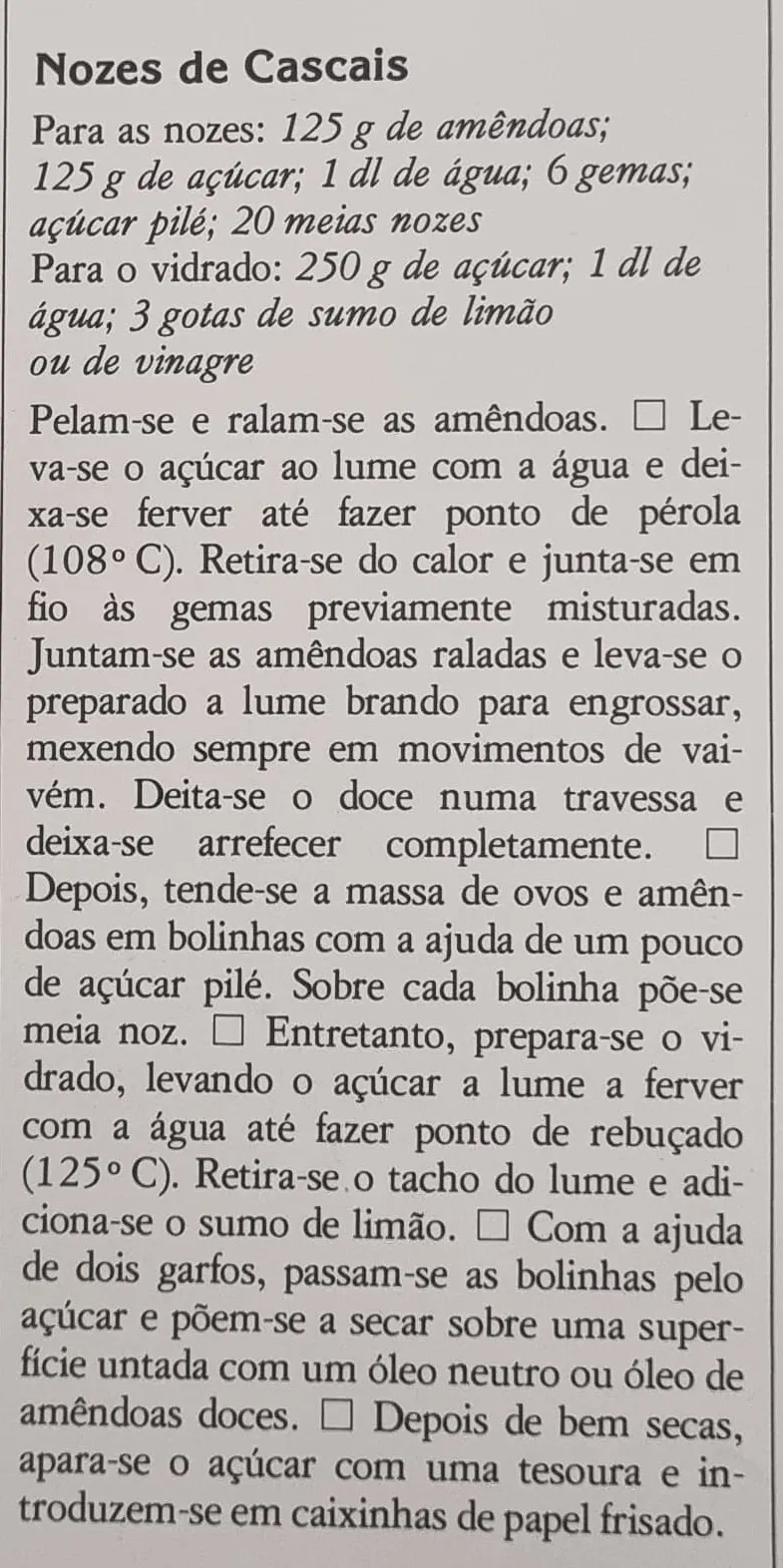

For a traditional sweet like nozes de Cascais to go through an official qualification process by the municipality, there needs to be a relatively standardised recipe. However, community-based recipes naturally evolve over time, with people adding or removing ingredients throughout the years.

“Formalising a recipe is always a risky process,” explains João Pedro Gomes. “Because once it’s written down in a famous cookbook, that version suddenly becomes the authentic one. Nozes de Cascais offer a fascinating case study—one of Portugal’s most renowned traditional cookbooks, Cozinha Tradicional Portuguesa by Maria de Lourdes Modesto, published in 1981, lists a recipe for them. But the book was likely based on research from the 1960s, a period when there was already a movement to preserve traditional recipes in response to globalisation and Portugal’s growing openness to the world.”

“What’s particularly interesting,” he continues, “is that Modesto’s version includes almond flour—an ingredient that, for most people today, isn’t associated with nozes de Cascais at all.”

Earlier recipes, such as those found in Grande Enciclopédia da Cozinha (1965) and one of the oldest recorded versions from Culinária Portuguesa (1936), refer to them as nozes recheadas (stuffed walnuts) and make no mention of almond flour. Some publications include almonds, others omit them. There’s even a manuscript housed in Torre do Tombo, often linked—without any actual proof—to a convent, that states the recipe doesn’t require almonds but then offers an alternative version that does, suggesting this was common practice.

“We tend to treat recipes as sacred, which makes these debates incredibly complex,” explains João Pedro Gomes. “For instance, after Maria de Lourdes Modesto’s Cozinha Tradicional Portuguesa formalised the almond version in 1981, just three years later, another major collection, Tesouros da Cozinha Tradicional Portuguesa by Maria Cancela de Abreu (1984), dropped the almond flour entirely.”

Despite these variations, the key ingredients that seem to have solidified over time are walnut kernels, egg yolk, water, and sugar. The Cascais Food Lab even has instructions for recreating this "complex" sweet at home. Throughout the years, several establishments have carried on the tradition—from Antiga Casa Faz Tudo to Casa da Laura - Pastelaria Almeida and, more recently, Pastelaria Bijou, which closed at the end of 2024. Another local landmark was Maria do Carmo’s bakery, which sold nozes de Cascais at Mercado da Vila and became a household name.

“Each recipe varied slightly from house to house—things like the caramel consistency changed,” Gomes notes. “And that’s completely natural and healthy in a community-driven tradition.”

As part of his research, he conducted a survey among locals. Out of 401 respondents, 289 recognised the sweet, and 194 claimed to know how to make it. Interestingly, 48 mentioned almonds as an ingredient, 22 included lemon—despite no known recipe featuring it—and 20 speculated that the sweet could have originated in Porto.

“There was this idea that the dough balls were shaped by hands dipped in Port wine,” he says. “But when I mentioned it to the producers, they were baffled—‘How do people think you could handle egg-based dough with wet, sticky hands? It would all fall apart!’”

Another lead now being explored, fuelled by fresh testimonies from the community, is a possible link between nozes de Cascais and the nozes douradas of Galamares, in Sintra. With a nearly identical recipe and an origin traced back 10 to 15 years earlier, they may well share a common past.

“Food traditions don’t follow administrative borders,” Gomes points out. “These days, we actively avoid the term ‘regional foods’—instead, we talk about territorial foods, which can span multiple municipalities or even regions. We keep hearing things like, ‘My grandmother used to make them,’ or ‘My aunt knew someone who did,’ and, of course, ‘What about the nozes from Galamares?’ We’re trying to bring all these pieces together.”

Time will tell—so it’s worth waiting to see what emerges. “We’re gathering these community insights to build a clearer picture. There’s still a lot to define about this tradition, and a few more months of research could give us a much better understanding of what really shaped nozes de Cascais. It’s a fascinating local phenomenon.”