In the hemisphere of Hong Kong’s gay-movie industry, Danny Cheng Wan-Cheung, or better known by his working name Scud, is quite the man. The Chinese director, who has created a signature out of dreamy montages and provocative storylines, has been making gay movies for ten years—many of which you may recognize and have actually seen—including City Without Baseball (2008), Amphetamine (2010) and Utopians (2015). Now that his latest film has opened in Thai theaters, we decided to catch up with the prolific director for a quick chat.

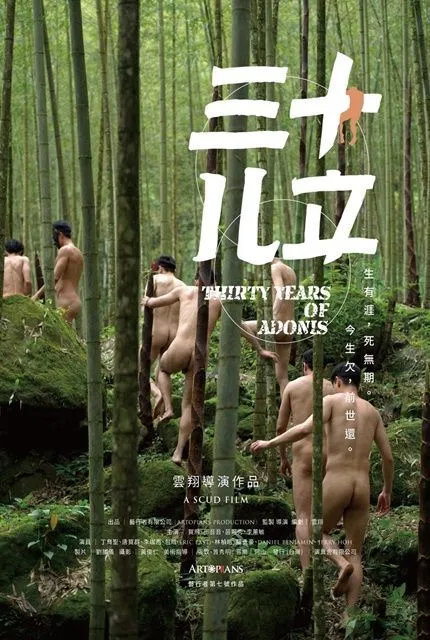

30 Years of Adonis is your seventh feature film, but it’s probably the first to show in Thai public theaters. What is it about?

It’s about an up-and-coming movie star. But somehow, his life detours into becoming a male sex worker. He thought it was fine because he wanted to take care of his long-ailing mother. He thought it didn’t matter, ‘I’m a man, I can always reject what it’s not, what I don’t want to do. And if I just do something to make people happy, it’s no big deal.’ But then, it’s faded into a miserable life, and in the pain, in the agony of that, he regrets. This film is about karma, about samsara and also about our eventual question on the meaning of life—how should we live or why we’re alive, and why are we moving on after everything. This has become more and more in my thought as I’m getting older and older approaching the end, so my films will be more and more about death, and afterlife.

Why do you think turning 30 matters so much?

30 years old is a very important mark in life. When you reach 30, you’re supposed to be mature enough, established enough, and know the direction of your life. That is what we say in Chinese: San Si Er Li, which is the name of the film in Chinese. It means, when you are 30 as a man, you are established. Because of this, a lot of young Chinese men would see 30 as a very important line, a very important milestone in life. The number 30 also happens a few times in the film, and by the end of the film you know why it means so much.

Most of you films involve nudity, gay sex, drugs, and depression. Why do these issues intrigue you?

Because I want to do something that no other people have done. That’s my value, that’s what I can leave behind to the world. Since few people are doing that, especially in Asia, I did that. And you see what happened after I started doing that? Now in Asia—Korea and even Thailand—filmmakers have begun to make a lot of jeopardy content. I happy to say that, more or less, if I pioneered all that.

So in general, a gay man still lives a more difficult life than so-called normal people.

Why do gay lives in your films are usually portrayed as so depressing, or dark?

They are. Let me tell you, they are. I actually listen to [this kind of] stories all the time. You know, I cast actors all the time and sometimes beautiful actors, even though they’re not into acting, they still want to see me to tell their stories. Let me tell you how many times I’ve heard stories like, his boyfriend took his life, sometimes in front of him. These sorts of thing you don’t usually expect them to happen often in life, but they happen very often in a gay’s life. So in general, a gay man still lives a more difficult life than so-called normal people. So that becomes why my films, they seem, there are many sad stories. Because there are more sad stories that I’ve heard more than stories with happy-endings.

So you’re saying your films are reflections of the lives of gay men...

Almost each of them has an 80-90% blueprint in real life. I want to insist on that so I don’t have to defend my films. Sometimes, people say the film is ridiculous, you can’t really have that in real life. I can tell you, it did happen like that. Everybody watches the film that’s packaged for a wide format. But that’s not what life is about. Most lives are not like that.

When you live differently from the so-called mainstream, you’ll have more adversity to face.

Your films, as well as other gay films from Hong Kong, give us the impression that gay life in Hong Kong is difficult and miserable. Is that accurate?

It is. And my stories are not only about Hong Kong but also about China. [Gay life in] China is even more difficult. Life’s all the same, everywhere. When you live differently from the so-called mainstream, you’ll have more adversity to face. But then, with so much pain in your life, it always makes life more meaningful. It’s always what I believe. Pain gives you substance. I would rather live a painful life than a normal, uneventful life—the so-called easy, happy life. And at the end, life will be gone. And if you don’t leave behind something, if you don’t leave a mark during your life, you’re not even worth it.

30 Years of Adonis is now streaming on Gagaoolala. Read more info about Scud and his films here.