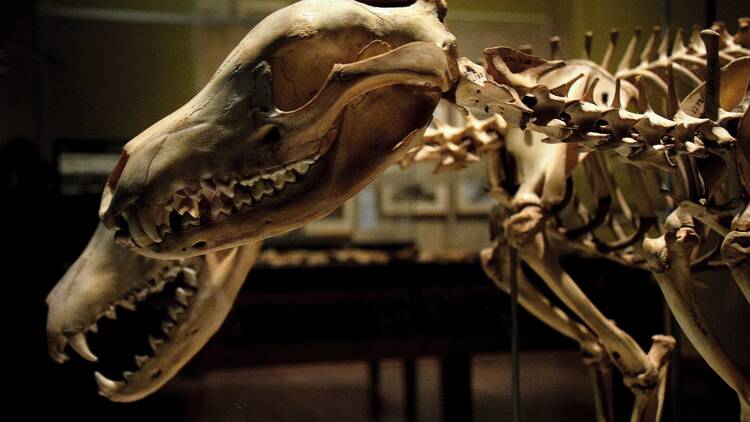

Almost 100 years have passed since the thylacine, commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger, was declared extinct. If you do the maths, it means that only a tiny fraction of Australia’s population has ever existed at the same time as the thylacine, the largest marsupial carnivore on Earth. But maybe not for long…

The Tasmanian tiger could make a comeback within the next decade, thanks to groundbreaking advancements in what promises to be the largest and most ambitious de-extinction project to date.

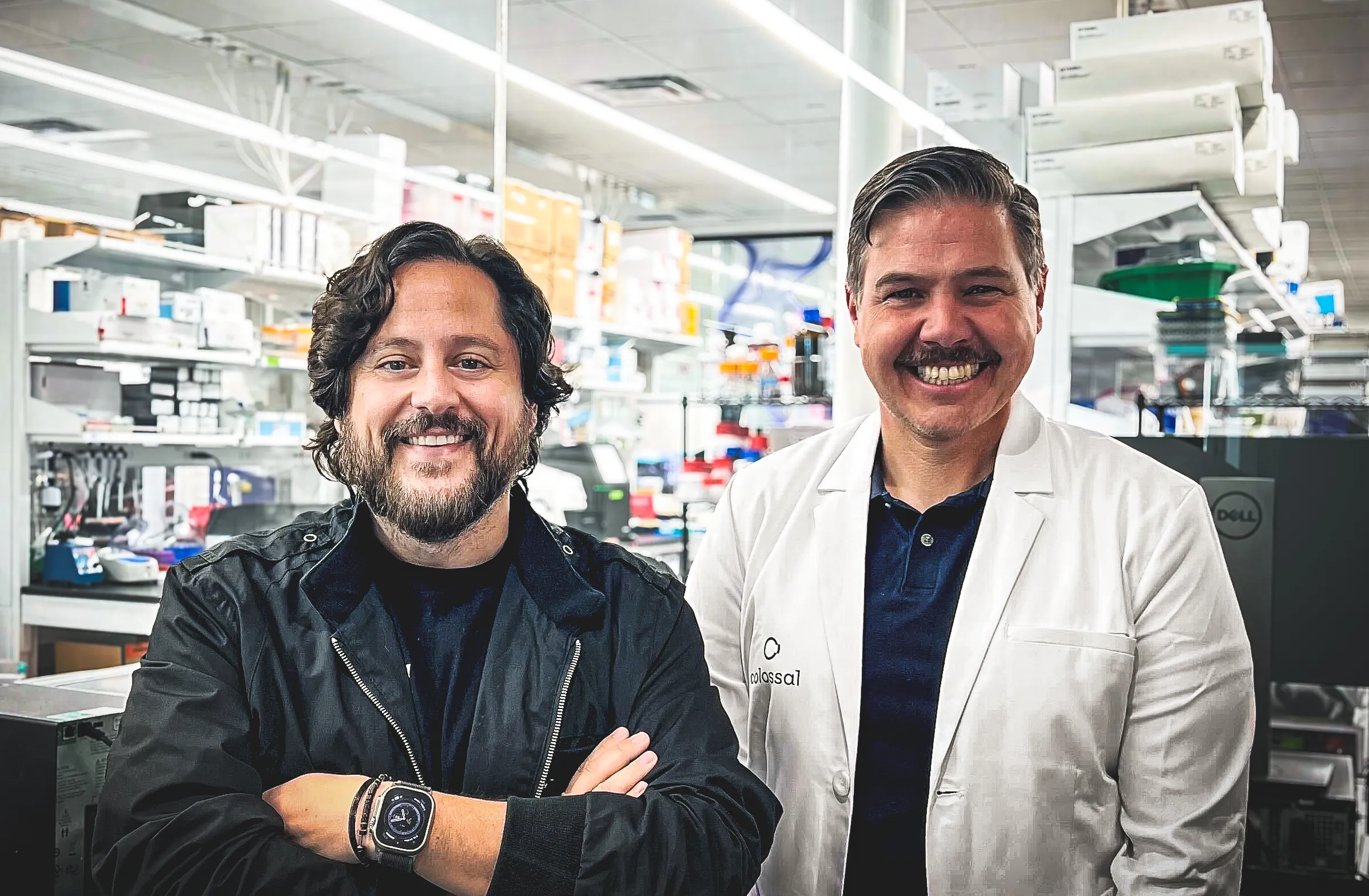

In 2022, scientists from the species preservation company Colossal Biosciences launched a major initiative aimed at bringing the thylacine back from the dead. Backed by some of the world’s biggest celebrities like the Hemsworth brothers, Super Bowl champion Tom Brady and superstar Paris Hilton, this marks the first time a project of this scale has ever been undertaken – with the end goal of reintroducing the thylacine back into Tasmania to protect the local ecosystem.

Given their relatively recent extinction, many thylacine specimens are exceptionally well preserved, allowing Colossal and its team of scientists across 17 global labs to develop precise genomic blueprints for the thylacine’s return. Co-founder and CEO of Colossal Ben Lamm estimates their DNA sequence for the thylacine is 99.9 per cent accurate, with much of this groundbreaking research taking place right here in Australia, in partnership with the University of Melbourne.

“We found some incredibly well-preserved samples with big chunks of DNA left in them that enabled us to do a complete build of that genome,” says Colossal thylacine lead and University of Melbourne professor, Andrew Pask. “That's challenging even for living animals, let alone for an old specimen like these thylacine ones.”

The researchers are currently comparing the thylacine genome with that of its closest living relative, the fat-tailed dunnart, to identify which genetic traits are unique to the species and which are shared among the entire dasyurid family. Next, they plan to employ gene editing techniques to modify the genome of the fat-tailed dunnart, having already made more than 300 thylacine-derived genetic edits to dunnart cells grown in the lab.

“What Colossal has already done in the last 18 months, in pushing genome engineering further than anyone else has done on the entire planet in such a short period of time, going from making a couple of edits to making 300 edits, is vastly unheard of,” says Pask.

In the coming years, Colossal will use assisted reproduction technologies to induce ovulation in the fat-tailed dunnart, which will serve as a surrogate for the thylacine de-extinction project.

Both Lamm and Pask are confident they can meet the ten-year timeline they initially set for the thylacine de-extinction project in 2022.

“Given that we have a 13.5-day gestation versus 22 months for mammoths, it's very possible that not only will we see our first thylacine within the decade, but we could see it much sooner,” says Lamm.

If successful, the scientists aim to collaborate with Indigenous partners and the government to rewild thylacines back in Tasmania.

“The thylacine was so important in maintaining that ecosystem in Tasmania, and that's because it's at the top of that food chain,” says Pask. “When we hunted them to extinction, there were no other animals to fulfil that same role in Tasmania, nothing else to take that apex predator position, so it really destabilised that entire ecosystem, and things like the devil facial tumour disease, which nearly wiped out the Tasmanian devils.”

Colossal’s success in developing de-extinction technologies could play a vital role in addressing the global extinction crisis.

“We no longer have to think of an animal being extinct as gone forever,” says Pask. “If there's a real need to replace an animal back in an ecosystem, we actually have the technologies now to bring those species back.”

These technologies could also be used to re-introduce healthier genomes from centuries past into existing populations of species, like the koala. You can find out more about Colossal’s thylacine de-extinction research here.