From the scales of a 19th-century Asante kingdom chief to a greasy spoon café in Peckham in 2010 is a remarkable journey for a brass goldweight to make. Measuring 2cm x 1.5cm x 1cm, the rectangular cuboid has an abstract pattern that vaguely suggests the sacred Asante Stool. It is embellished with few other decorative qualities. Yet imbued within the scarred metal and finger-worn edges is a story: the power of an Asante chief, decades of turbulent war with the British, a journey through the scrubland of Ghana, a flight to England and, most recently, a trip to a café in Peckham.

Partly responsible for the voyage of the artefact is Tom Phillips, a distinguished painter, sculptor, composer, author and avid Ghanaian goldweight collector. Speaking a day before travelling to Berlin to launch his book African Goldweights, he explains the attraction of the weights.

“I think they are beautiful objects,” he enthuses over a plate of liver, chips and beans. “They are incredibly delicate, and made using a forgotten method with beeswax. You try making them – it is very complicated”.

Although the one now in my hand has a relatively simple design, the weights that were used to weigh gold-dust currency between the 15th and 19th centuries in the Asante Kingdom (and among other parts of the Akan entholinguistic group) come in a vast variety of different styles.

The Asante region might have been restricted to West Africa, but a clear Muslim influence can be seen on early designs from the 16th century. The individual stylings of each piece, however, are primarily down to the whim of the goldsmith whose job it was to make the goldweights out of brass. As we walk around Tom’s studio, hundreds of weights on every mantelpiece and flat surface can be seen depicting birds, beetles, tortoises, shells, fish, drums and human figures eating, drinking, playing musical instruments, hunting and, yes, weighing out gold. And while many are representative motifs, or illustrative of proverbs, many of them are decorated with defined patterns. “It is abstract art, made three or four hundred years ago,” Phillips points out.

Yet for centuries, ethnologists, anthropologists and art-collecting Europeans all but ignored these beautiful objects. The weights were not used for rituals, had no religious significance other than when the chiefs were displaying their wealth, and their ubiquity meant few collectors were interested. Their significance is huge, however. “Asante goldweights are one of the only secular pieces of old African art that exist,” Phillips argues.

The Asante (a spelling generally preferred over Ashanti) are an ethnic group from modern Ghana, and part of the West African Akan ethnolinguistic group. It was the Asante who built up one of the largest and most powerful kingdoms in West Africa, with Kumasi as its capital. During the 1670s, when powerful leader Osei Tutu brought together a federation of clans – many of which were working with Europeans to expand the slave trade – a confederacy was created.

The kingdom soon expanded into a domain that spanned current-day Ghana and Ivory Coast, largely with the aim of controlling the gold trade and trading with the Europeans. By 1750, the Asante kingdom was around 100,000 square miles (258,000 square kilometres), slightly larger than Ghana today, and had a population of between two and three million. In the 19th century, British traders and government colonialists aimed to demolish it. There were five main conflicts over the century, with the final confrontation now known as the War of the Golden Stool.

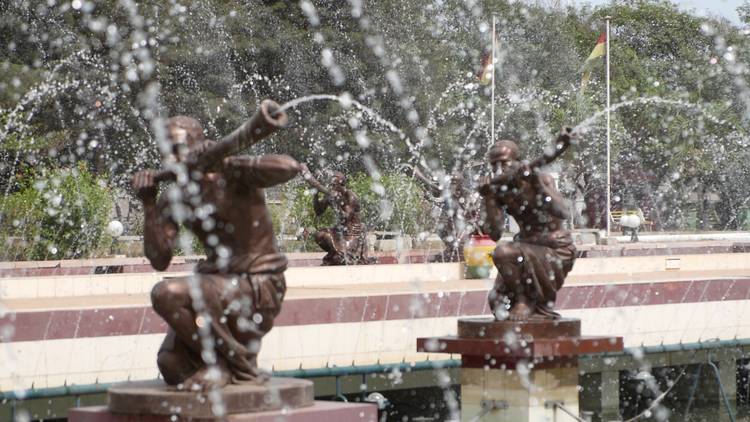

The legend of the Golden Stool – a motif that can be seen across Ghana, not least on the national flag and in the design of the remarkable government building – is at the heart of Asante culture. It is said that the Golden Stool, sika dwa in Akan, descended from heaven and landed in the lap of Osei Tutu, thus coming to symbolise the strength of the Asante people. The golden stool is still said to exist, although its whereabouts remain unknown since Sir Frederick Hodgson, Governor of the Gold Coast, demanded to sit on it in 1900, thus starting the war – won by the British by 1902 – which eventually incorporated the Asante territories into the Gold Coast.

It was around this time that the goldweights ceased to be used for their stated purpose – gold dust, rare after the British incursion, stopped being the Asante currency. However, according to Phillips, the goldweights still retained some of their local prestige even into the 20th century.

“It would not be uncommon, as the Asante began to flourish as a nation in the early 18th century, for the head of a family to have a few dozen weights at least,” he writes in African Goldweights. “This in part accounts for the huge number that have survived. Another factor was their role as heirlooms and the consequent care with which they were kept even long after they ceased to be of use for trading.”

Today, many of the goldweights are in the hands of collectors and specialised dealers, in Europe as well as in Ghana. Seeking out authentic goldweights in Ghana is still possible, although finding the right person can take a considerable amount of patience and a lot of asking around in markets such as the Art Centre. And if you’re fortunate enough to come across any genuine articles, spend a moment in appreciation – in historical terms, they’re worth their weight in gold.

Tom's book African Goldweights: Miniature Sculptures from Ghana 1400-1900 is available now on Amazon and other online retailers. (Hansjorg Mayer ISBN-10: 0500976961 ISBN-13: 978-0500976968)