There are plenty of reasons why you might dislike ‘I’m Not There’, Todd Haynes’ crazy jigsaw of a sort-of biography of Bob Dylan that breaks all the rules without writing any new ones. If you’re a Dylan nut, you might object to the loose telling of the facts – ‘What? You’re telling me that Suze Rotolo and Sara Lownds were the same person and that Dylan fathered two daughters with her?’ That kind of thing. Alternatively, if you know next to zilch about Dylan, you might find yourself all at sea amid Haynes’ torrent of wink-wink references and playful, fold-in, fold-out approach to events in the artist’s life. And, finally, if you’re one of those who can’t stand Dylan’s songs or hear anything in them beyond an excoriating whine, well, sorry, but you may find yourself reaching to employ your popcorn as earplugs: the film is packed with his music, performed by the man himself and a clever line-up of cover artists, from Sonic Youth to Cat Power to Calexico.

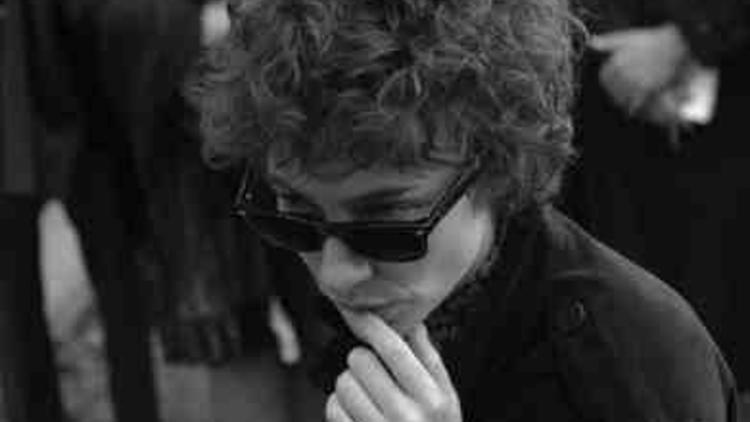

The recipe is famous. Six actors. Seven Dylans – none of them called ‘Dylan’. Colour. Black-and-white. Backwards and forwards. Forwards and backwards. Selective memory. Abstract concepts of character. The deconstruction of images and speeches. Marcus Carl Franklin, a 13-year-old African-American actor, plays the spirit of a teenage Dylan meshed with his hero Woody Guthrie’s vision of the highways and byways of the depressed 1930s nation. Heath Ledger is a late ’60s film star who is wrestling with a failing marriage to a celebrated painter (played by Charlotte Gainsbourg). Christian Bale is two Dylans: first Jack, a protest singer in early ’60s Greenwich Village, then in the late ’70s John, an evangelical preacher in the dreary suburbs. Richard Gere is a reclusive Bob, framed in the territory of Peckinpah’s ‘Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid’ and playing Billy as a disguised, wandering survivor of Garrett’s blood-lust. Then there’s Cate Blanchett, all cheekbones and mercurial, as Pennebaker’s black-suited Dylan and who exists in a world where verité meets Richard Lester meets Fellini. And, lastly, there’s Ben Whishaw who evokes Dylan’s love of Rimbaud and hatred of questioning with his back to the wall in an interrogation set-up.

Whatever your prejudices, if you’re sick of films that treat the lives of artists – musicians, especially – in the same, predictable fashion, then you should thank the high heavens for ‘I’m Not There’. Too often, we watch and groan as artistic inspiration is presented as a corny eureka moment (I still haven’t forgotten the sight of paint dripping to the floor of Jackson’s lavatory in ‘Pollock’) and domesticity is offered as a barrier to expression and later as a refuge from the fallout of that expression. Too often, too, a film claims to offer the last word on a life. Haynes is pretending to offer no such thing. His approach is honest: it’s the reflection of a life through the mirror of experimental film. It’s an acceptance that contradictions and interpretations and even mistakes are more acceptable than a biography preached as if from a pulpit. This is a typical blurring of form from a director who has already rethought the lives of Karen Carpenter and David Bowie and who looked afresh at the work of Douglas Sirk in ‘Far From Heaven’. It’s not a perfect experiment. At several points, it loses its strange rhythm, only to be rescued by the music itself, which is always well chosen and placed. At other times, Haynes is too much in debt to his sources, such as Pennebaker’s films, or he fixates for too long on a single thought, such as that which sees Gere wandering through a carnivalesque landscape in the late nineteenth century. But the film’s best ideas – such as Franklin’s ‘Woody’ strumming in the lounge of his proud, white adopted family or Ledger’s ‘Robbie’ wandering out of a Nicholas Ray-style film-within-a-film to fall in love with Charlotte Gainsbourg and later to reject her – are smart, playful and ensure that as a fractured, highly personal biography, ‘I’m Not There’ is full of intriguing arguments, movements and performances.