What is shunga, actually?

Though the earliest shunga (literally ‘spring pictures’, with ‘spring’ being a Japanese euphemism for sex) can be traced back much earlier, the art form is most closely associated with the Edo period and its ukiyo-e, woodblock prints that depicted Edo’s hedonistic ‘floating world’ of geisha, kabuki, sumo – and sex.

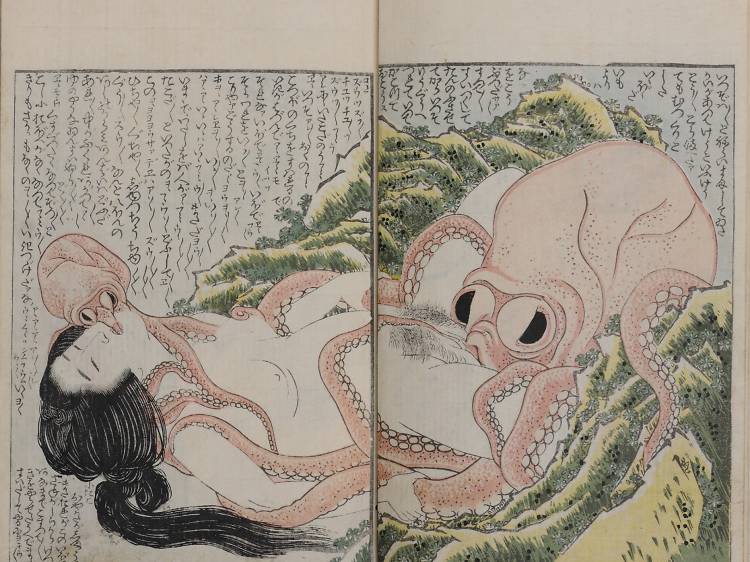

Shunga was painted by some of the best ukiyo-e artists of the day, including Kitagawa Utamaro and Katsushika Hokusai (Hokusai’s most famous shunga, which features some octopus-on-woman action, was the subject of a 1981 film titled ‘Edo Porn’). Shunga was in demand, and one commission from a wealthy buyer would reportedly keep an ukiyo-e artist eating for months.

One, ahem, standout element of shunga is the exaggerated genitalia. This flourish was not, in fact, ukiyo-e artists bragging about the size of their, uh, brushes, but rather an expression of the genitalia as a ‘second face’, one that, unlike the face presented to the public every day, represents one’s true primal desires – hence both the similarity in size and often unnatural physical proximity to the noggin’.

Another unique shunga element: both partners are usually fully (well, almost fully) clothed. Unlike in the West, where bare flesh was seen as simultaneously tantalising and taboo, men and women of Edo-era Japan saw each other in the nude regularly at mixed baths and the like. If anything, it was more appealing to see men and women in shunga clothed, as it helped to identify the characters’ walk of life and to emphasise the parts that were exposed (as if they needed any more emphasising).

Photo: ‘Kinoe no Komatsu’ by Katsushika Hokusai