Nineteen-year-old glazier Danial is standing on Bayswater Road late on Saturday night and isn’t going anywhere. Not now, he says, and not when the lockout laws take effect. “I work every day just to come here on the weekend with my boys,” he tells us as his mates gather around after a rousing chant of “Fuck the lockout!” for the benefit of a TV news crew. “These are my family and if you shut the Cross down you’ll be shutting down a lot of lives.”

We’re at the corner of Kellett Street, just before the strip of terrace clubs that includes Candy’s Apartment and World Bar. Shiny-eyed kids sprawl against a wall and burly guys in singlets barrel through, pinballing off the crowd as they go. Danial approaches as we’re interviewing his mates, most of whom travelled in from Campbelltown by train or in cars. It’s the last weekend before the state government’s new legislation will cut their nights short and they’re gearing up for a blinder at Candy’s.

“When I first turned 18, I went out to the Cross 42 weeks in a row and I’ve never seen one fight,” says Danial. He adjusts his cap as he tells us the move is going to be catastrophic for businesses and explains why he comes to the Cross: “There are good things in Campbelltown – we go there Friday nights – but Saturday we want to leave our problems back there and party.” What will he do when the new laws take hold? “We’ll come, we’ll drink earlier and we’ll cause more havoc than what we would have. This is our Cross, this is our home.”

We meet Danial again two weeks later, on the second Saturday night after the introduction of the new laws. It’s a little after midnight and he’s sitting on the floor on Bayswater Road, exactly where he said he’d be, but after a day at Future Music Festival, he is “in no condition to talk”. And he’s not sticking around. “I didn’t come here last week,” he says to our surprise, “and I’m never coming again.” When we ask what changed, he tells us to take a look around. “Look at the streets – it’s so dead here. I’m never going to the Cross again.”

"Look at the streets - it's so dead. I'm never going to the cross again."

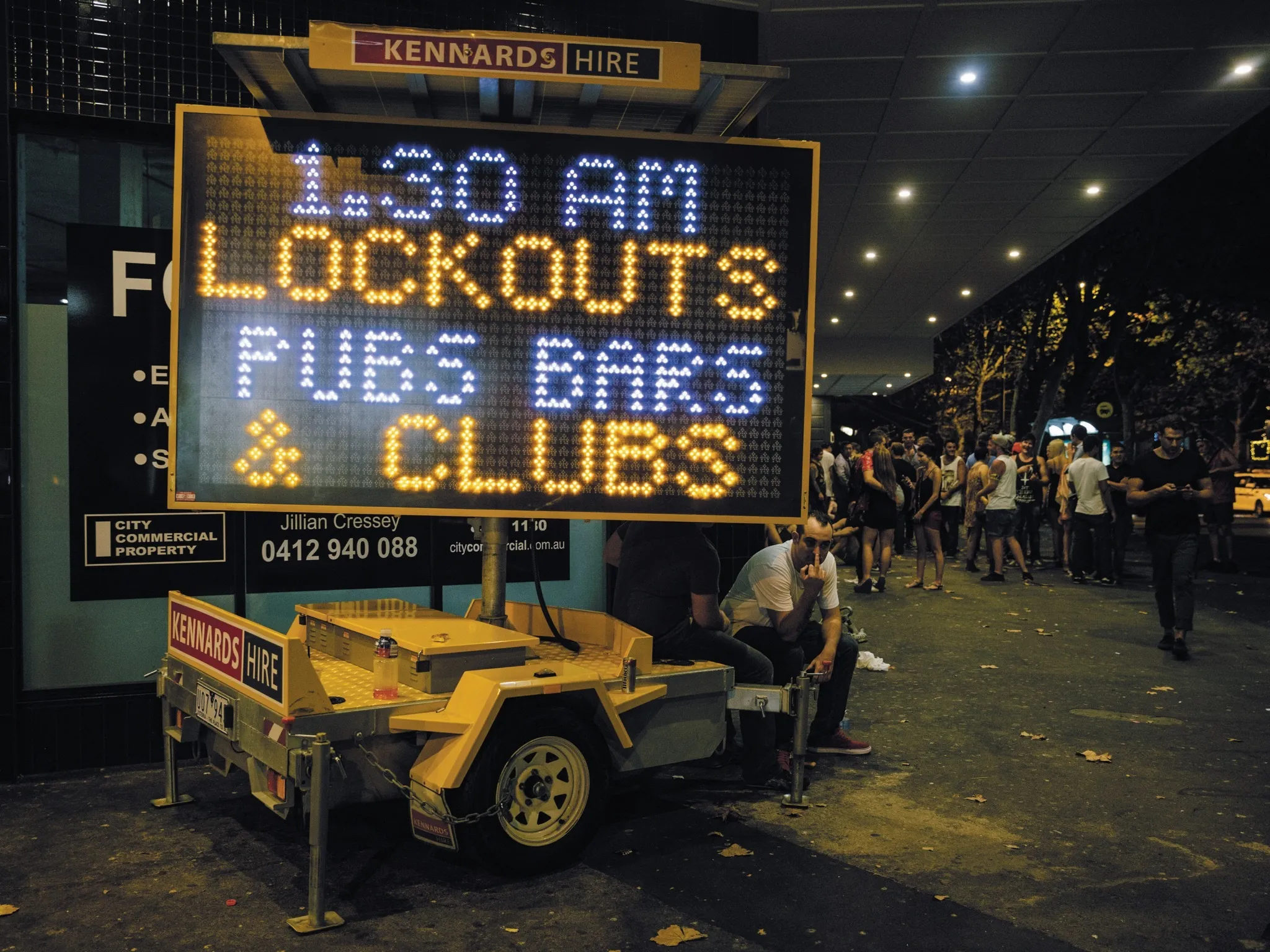

“So dead” was an exaggeration. To our eyes the streets were full and that familiar Kings Cross crackle still in the air, fuelled this night by the tribes flowing in from Future and a Sydney FC vs West Sydney Wanderers game. But at almost precisely 1.30am, “dead” became more fitting. The sidewalks of Bayswater Road were quickly deserted as people crammed into clubs, as was Oxford Street where a large ‘Be in early, stay late’ sign looms over the notoriously late-trading Courthouse Hotel. We caught a couple of Danial’s friends who hadn’t made it into Candy’s. “It’s the shittest laws ever,” one told us. “We couldn’t even get into the line. We’re facing, like, five hours waiting for trains.”

Danial (centre) and his mates Photograph: Daniel Boud

When Time Out Sydney went onto the streets pre- and post-lockout, the immediate effects were obvious: quiet streets after 1.30am, a bit of a rush to get cabs at 3am and a lot of unhappy revellers at all hours. But that much could be predicted, and had been. The untold story of this late-night drama is the new legislation’s longterm effect on the city. How will businesses adjust? Will punters move elsewhere? Will the laws actually reduce violence? And, crucially, what happens to our international reputation when Sydney – Australia’s own city that never sleeps – can no longer stay up past its bedtime?

The O’Farrell government’s Liquor Amendment Bill 2014, passed by the NSW Parliament in February and put into effect just weeks later, is described by one major hospitality group owner we spoke to as “the most significant impact on the greater group of [Sydney hospitality] operators I’ve seen… I can’t see anything having been bigger.” By now you probably know the particulars: a 1.30am lockout and 3am last drinks across a ‘Sydney CBD Entertainment Precinct’ that stretches in a big yellow splotch from the Rocks to Central with exemptions for the Star, Barangaroo and small bars (maximum capacity of 60); a statewide 10pm closing time for bottle-os; and fines of up to $11,000 for breaches. Parliament passed new “one-punch laws” around the same time, with mandatory minimum sentences of eight years for offenders intoxicated by drugs or alcohol, and gave police power to ban “trouble-makers” from pubs and bars in the precinct for 48 hours.

Premier O’Farrell tells Time Out via e-mail: “The NSW Government makes no apologies for these tough new measures. We heard the community’s call for action and we committed to doing all we can to reduce the number [of] drug and alcohol-fuelled attacks on our streets.” The package is designed to send “the strongest possible message”.

The package has proven vulnerable to all sorts of attacks. Many are quick to note that the tragic instances that prompted the community’s outrage both happened before 1.30am – Thomas Kelly, 18, was fatally “king hit” while walking with his girlfriend on Victoria Street just after 10pm in July 2012; Daniel Christie, also 18, was “coward punched” near the same spot at 9.10pm last New Year’s Eve. Then there are the stats that show voluntary area liquor accords and current regulations might have been working, with an 8.2 per cent drop in alcohol-related non-domestic assaults in the Sydney local government area between 2012 and 2013 (to be fair, there are stats out there to build cases on both sides). Some say calling last-drinks at taxi change-over will lead to chaos, while others puzzle over why the government is still not introducing 24-hour weekend trains to help with street congestion.

Then there are the teething problems. Most venue owners we spoke to said they weren’t consulted about the new laws, and weren’t prepared for their implementation – at a meeting between city licensees and the Office of Liquor, Gaming and Racing before the first weekend, a discussion ensued over whether venues in the precinct, but with a side door on a street outside it, were exempt. “It was a shemozzle,” says our source. Club-goers are similarly finding their feet, with some being locked out unawares after going for a smoke or helping a wobbly mate into a cab.

On one of our nights out we met Caner, 21, who paid $25 to get into World Bar for just ten minutes; he’d left to go to an ATM and was not allowed back in. Caner’s phone was flat, leaving him no way to reach friends inside. “I’ve got no idea what to do,” he told us, waiting on the sidewalk. “If they don’t come out I’m just going to catch a train back to Penrith. But how do you know nothing’s going to happen when I’m by myself?”

–

We’re sitting in Clover Moore’s office at Town Hall House and the Lord Mayor wants to talk food trucks. The nine trucks currently on the streets have drawn “a fabulous response” she says, and the City is now going to issue contracts for up to 50 mobile venues. Time Out thought we were here to talk violence in Kings Cross, but the Lord Mayor says that it’s all related.

The trucks are the latest in a suite of projects Moore has spearheaded to enliven the city’s night-time economy, moving it away from just a place to get wasted to something more “civilised”: 2008’s small bar reform opened the door for the current 70 small bars in the City; the abolition of the Place of Public Entertainment (PoPE) license made it easier for live music venues to open; and council’s Live Music Taskforce will, hopefully, strengthen the gig offering in the city. There have been measures to improve safety, too, Moore adds, such as more LED lighting, ‘late night precinct ambassadors’ and portable toilets (“We know having those is good because we remove bathloads of pee – bathloads!”).

"At no point did we think about the culture we want."

Is the new legislation a blow to all that work? “It is,” Moore admits, and says that renewable licences for venues, to encourage compliance and punish poor management, would be “much more our approach” than blanket lockouts. “The concern many have about the new law is that it seemed very desperate, it didn’t seem to be considered,” says Moore. “The focus was on the Premier and he had to come up with something.” Still, the City will continue working to make Sydney an exciting place to be at night, and not just to get boozed. The City’s OPEN SYDNEY strategy plan issues a hope that by 2030 more than 40 per cent of people using the city at night will be over 40, and that 40 per cent of businesses still open will be shops.

It will be a hard goal to reach if businesses currently bringing people into the city at night don’t survive the lockout. Which is a real possibility, according to those running them. Anthony Prior is the co-founder of the Keystone Group, which runs Bungalow 8, the Loft and Cargo at King Street Wharf and the Sugarmill in Kings Cross. He’s noticed a stark lack of turnover on Saturday nights after 1am; there’s a natural flow of people leaving but no influx to replace them. “So you don’t replace any staff leaving after 1.30am,” says Prior. “I’ve been speaking to other colleagues and we all agreed that between 3am and 3.15am, the writing was pretty much on the wall.”

Which is fine for Keystone – the group has a strong food offering and day trade and isn’t too dependent on late-night revenue. “But I can see smaller businesses in Kings Cross and the city whose peak hour is 11pm to 3am being in a really tough spot,” says Prior. Tough enough to force them to close? “I’ve heard stories of some people quantifying it up to a 70 per cent downturn. You can’t operate a business with that kind of downturn when you have the overheads that we all do.” A solicitor for the hospitality industry who’d fielded calls from city-based pubs in February told industry website the Shout: “Many of the smaller hotels estimate that their turnover is likely to reduce by as much as $20,000 to $40,000 per week – that’s $1 to $2 million per year… These numbers will very likely result in forced closures due to non-viability.”

Photograph: Daniel Boud

Are people moving outside the precinct? Assistant Police Commissioner Mark Murdoch says he’s seen no evidence of new crowds at venues on the cusp of the Cross and CBD after lockout, but one Newtown owner tells us revenue is already up at his late-trading pub.

It’s not just bars and clubs in the precincts worried: a worker at a Darlinghurst Road tobacconist, who also does shifts at the Kings Cross McDonalds, told us Saturday-night business had dropped dramatically at both. A kebab shop owner tells a similar story, saying he’ll have to shut earlier now that Sunday morning trade has fallen by more than half.

For Jimmy Sing, co-owner of Liverpool Street’s Goodgod Small Club, food and alcohol sales are not the primary concern. Goodgod is the kind of venue the Lord Mayor would like to see flourish in the city: it has a clean record, it promotes local music and its focus is on throwing shapes more than throwing back. But the new laws are still disruptive. “Programming’s been a real puzzle for us,” says Sing. Where normally he’d schedule a couple of live acts and a bunch of DJs on a club night that might kick off at 11pm, he’s now having to strip the offering right back.

That means fewer door sales from people coming to see different acts, and fewer opportunities for musicians. “For us it has been about finding a model where we can put on bands that aren’t going to be 100 per cent sell-out rooms – we can experiment – that can be subsidised by a really popular international DJ later. We’re looking at having to cut that back to five. That’s a loss for everyone.”

Groups such as music industry organisation Music NSW are pushing for exemptions for entertainment venues, and the government seems at least open to the idea of refining the law. George Souris, Minister for Hospitality, notes that the lockouts will be subject to an independent statutory review in 2016. Premier O’Farrell told Time Out: “As I’ve said from day one, this package may require tweaking from time to time – and we will tweak it if there are ways we can make these new laws more effective.”

If a push for exemptions gains traction, one point of contention will be what defines “entertainment” – a band on stage? A DJ on an elevated platform? A guy in the corner on his Mac? Sing says the questions might have been asked sooner. “There’s an issue here of closing down spaces that have provided a solution to a positive late-night culture. At no point in the debate did we think about what sort of culture we wanted to maintain and to help foster in Sydney.”

–

Chris is at Pacha, the Ivy’s mammoth Saturday night party, a week before the lockout laws take hold. He’s 26, a structural engineer from La Perouse, and sure, he admits, he’s been in a few scrapes around town. They were mostly when he was younger and the worst happened just around the corner, he recalls… sort of. “We were drunk, we had no idea what was going on and three guys took advantage and hit us.” He doesn’t think the lockouts are too bad – “If you’re not in the club by 1.30am, what the fuck are you doing?” – but he doesn’t think they will work.

“There will always be trouble in Sydney, always,” says Chris. “Sydney is a mix of a lot of different cultures. The way it was described to me, and I agree, is that it’s like a zoo. People interpret other people’s attitudes and actions the wrong way and it’s human nature to get defensive. You mix all the animals into one cage and you’re going to get problems.”

Crowds in Kings Cross Photograph: Daniel Boud

Whether you subscribe to that theory or not, the coverage of one-punch deaths in Kings Cross and lockouts has certainly re-exposed some cultural fault lines. East vs West? It’s there in talk about the “kind of people” who come to the Cross on Saturdays. One young gay man from Alexandria waiting on Bayswater Road told us he doesn’t come to the area that much because “it’s either full of, like, angry Lebanese people or wogs or straight boys that have had too much to drink and get angry.” A 21-year-old girl from the North Shore speaking to us after a night at Darlinghurst’s Cliff Dive asked, “Why does everyone need to be punished for the actions of some Westie?” Later, describing “idiots” who start fights in the Cross, she demurred: “I don’t mean to sound like a stuck-up bitch, but basically they’re coming in from a fair distance.”

For true ugliness, as ever, you only need go online. A day after Daniel Christie was hit, someone anonymously set up a satirical Facebook page for Shaun McNeil, the tattooed, mixed martial arts-loving “Westie” charged with the attack. On one recent post linking to a news.com.au story about a Bidwill man who viciously killed a dog, ‘Shaun’ writes: “We sure know how to do shit out west we do”. The page has almost 1,000 Likes.

Many of the venue owners, promoters and DJs we spoke to point to a subtler and more interesting divide opening up: that between Sydneysiders who get what a late-night good time is about, and those who they say have no idea. “I think this was made black and white by the NSW police minister [Michael Gallacher] in parliament,” says Goodgod’s Sing, alluding to Gallacher’s contention in parliament that “the live music industry is dead”. “There’s actually been a really positive change in the city over the last two years with spaces opening up that present live music in different ways. It’s not just about a pub with a room that has three bands and it’s over.”

"Mix all the animals in a cage and you get problems."

Simon Caldwell, the FBi Radio host and stalwart Sydney DJ, has been vocally opposed to lockouts. He says, “I don’t think there’s a distinction made between drinking holes and nightclubs. The whole cultural aspect of nightclubs is still under a lot of people’s radars, whereas in Europe everyone respects that techno is part of the culture – it just is.”

That lack of understanding might damage the city’s international reputation. Sing says he has had talks with international DJs and bands coming through and “they’re in shock. Sydney has a reputation as a really fun-loving, energised city. A lot of people, especially in the dance world, know Sydney as a positive crowd that really looks after each other. This feels like a real shutdown of that.”

–

“Do you feel safe here?” We asked this question to everyone we spoke to on the street when reporting this story. The answers varied from “Yes, if I’m with the right people” to “I would walk from Kings Cross to Town Hall by myself quite happily right now.” One man said, “In a group, yes, and being gay you’re even more aware of your surroundings”; a young woman told us, “There’s safety in numbers but I’d never come here by myself.” Danial, our Campbelltown glazier, simply indicated around him: “Look at my boys: I am more safe here then when I am at home.”

People have been asking this question in Kings Cross and Darlinghurst for decades – when it was sly-grog swilling ‘Razorhurst’, when it was a wild R&R hotspot for US servicemen on break from Vietnam and when it was junkie central in the 1980s and ’90s.

Whatever the longterm effect of the laws, it seems certain that they won’t stop young people from wanting to go out and have fun. And drink. And Kings Cross, the city and the Rocks are the places they want to go to do it. Every city has its designated party zones, where there will always be a splash of vomit on the street and a crackle of danger in the air. That might be part of the appeal.

Maya, Chanelle and Cailyn wait for a lift home Photograph: Daniel Boud

We find Cailyn, Chanelle and Maya outside the Kings Cross Hotel. They are all 18, from Wollongong, and waiting for Cailyn’s dad to collect them – they missed their Future Music bus home and Cailyn had to make “the call”. They’ve never been to the Cross, and can’t go out tonight because Maya lost her ID. As we chat, a random guy grabs the girls into a tight scrum, barks a Rugby play, then walks off.

The girls look nervous, teetering at the edge of the action at the corner of William Street and Darlinghurst Road as if nervous to dive into an icy pool. Do they feel safe? “I just think Kings Cross is full of crazy people,” says Cailyn. “I just think of all the bad things that I’ve read about… But it does seem like fun.” Maya agrees. “I think it’s scary, and it’s always on the news, but I’m keen to come.” The planning then begins. “We should come in a big group have a whole night here and just sleep somewhere,” says Maya, turning to the others excitedly. “You have to experience Kings Cross at least once.”