It’s hard to ignore the impact of NYC’s thriving craft-beer scene, when even the corner bodega is stocked with a bounty of locally made suds. But what many drinkers don’t realize is that this windfall is not a revolution so much as a renaissance—a return to our rich brewing roots that extend all the way to the colonial era. A new exhibition at the New-York Historical Society, “Beer Here: Brewing New York’s History” (through September 2; nyhistory.org), offers an enlightening survey of the endless ways in which beer has ingrained itself into the fabric of the city. Here, curators Debra Schmidt Bach and Nina Nazionale walk us through some of the milestones in the annals of Gotham brewing, as well as the most intriguing artifacts you can expect to see at the show.

Beer rations

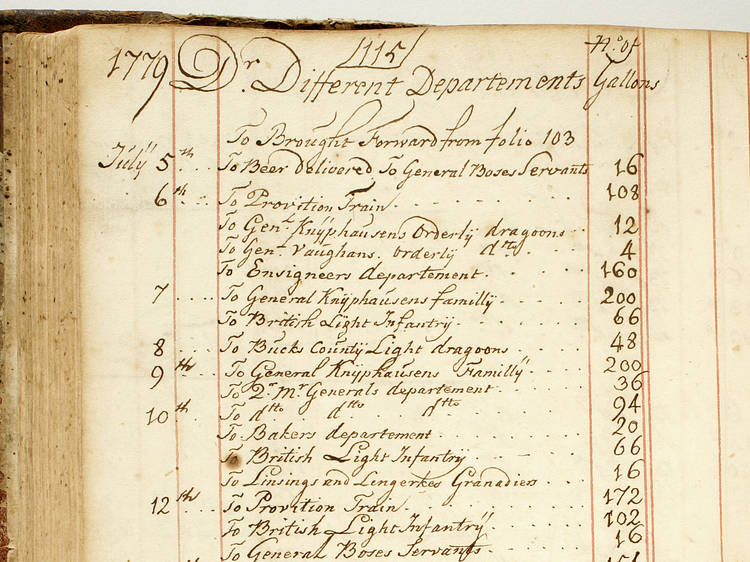

The exhibition begins with a look at colonial-era tippling and the nourishing qualities of beer, which at the time was often safer to drink than water. The beverage was so important nutritionally, in fact, that it was rationed for soldiers. A key artifact from this period is brewer William D. Faulkner’s daybook, used to keep track of his clients. “When you look at [the manuscript], you see evidence that he was providing beer to both the Continental Army and the British [during the Revolutionary War],” says Bach.

Water and waterways

One of the show’s most jaw-dropping images is a painting by Andrew Fisher Bunner depicting ice-harvesting operations on Rockland Lake, about 15 miles northwest of Manhattan, in the late 1800s. New York breweries—particularly those producing German-style lagers that require cold fermentation—were a major consumer of ice, which, prior to the advent of the mechanical refrigerator, had to be cut from lakes in massive sheets and transported down the Hudson River. In a section detailing the relationship between brewers and water, you’ll also see early-19th-century pipes made from hollowed-out pine logs, and learn how the 1825 opening of the Erie Canal amplified the cooperation between NYC brewers and upstate agricultural producers. “We want to show how things we take for granted today were not readily available in the city’s early history,” says Bach. As a major business interest, breweries were able to drive technological advancements and civic improvements that had implications beyond their walls.

New York’s hops supremacy

Today there’s a burgeoning movement toward local hops production in New York—Bronx Brewery is currently growing Cascade hops plants in community gardens in the borough for one of its beers, and shoppers at the Union Square Greenmarket can buy farm-to-glass home brews from Tundra Brewing’s Mark VanGlad, who grows all his own ingredients on a farm near Stamford, New York. Boosters of the revival will be heartened to know that New York was the country’s biggest hops-growing region throughout much of the 19th century. Here, you’ll see early hops-harvesting machinery on loan from the Cooperstown Farmers’ Museum and read stories about seasonal workers who tended to the crop—including a 14-year-old girl who kept a diary of her hops-picking adventures.

The arrival of lager

If you’re wondering how brands like Schaefer and Rheingold came to dominate the New York beer scene, look no further than the mass influx of German immigrants that arrived here in the late 1830s and 1840s. “Within 20 to 30 years of the Germans arriving, the predominance of beer being produced were in the lager family,” says Nazionale. Reproductions of fire-insurance directories from the time reveal the scope of the takeover: By the 1850s, breweries dotted Manhattan and Brooklyn. Many congregated around Yorkville and Williamsburg, and they were largely owned by Germans such as George Ehret and Jacob Ruppert. A New York Times trend piece in 1877 noted not just the supremacy of “lager beer,” but also the culture surrounding it. Beer halls and beer gardens were common, including the massive Atlantic Gardens at the corner of Bowery and Canal Street (“it was like an airplane hangar,” says Nazionale).

Temperance and taxation

The city’s cocktail nerds are well versed in the effects of Prohibition on tippling culture in Gotham. But despite its lower alcohol content than distilled spirits, beer didn’t escape the wagging fingers of local temperance movements in the 19th century. Downtown drinkers will get a kick out of a pamphlet from 1893 called “Liquordom,” in which one group mapped sections of the city “where lager reigns” (you’ll see 181 “lager beer saloons” between the Bowery and Norfolk Street alone, suggesting that the Lower East Side of the 1890s was every bit as sloppy as it is today). In addition to Prohibition, the exhibition details the history of taxation on beer in New York, which extends all the way back to the early Dutch settlers. A beer-specific excise tax levied in 1862, designed to raise funds during the Civil War, spawned the creation of the United States Brewers’ Association, to act as an advocate for the increasingly powerful industry. The charter membership was so dominated by lager brewers that German remained the official language of USBA conventions until 1875.

The age of Miss Rheingold

The breweries that managed to survive Prohibition—often by selling products such as near-beer (less than 0.5 percent ABV), malt syrup and ice cream—kept New York’s brewing clout alive into the postwar era, but the landscape was as homogenous as ever. This was the reign of big brewers and light lager, as well as the beginning of the beer marketing wars we’re familiar with today. One of the most famous campaigns was the Miss Rheingold contest, run by Rheingold Beer between 1942 and 1964. At the exhibition, check out Miss Rheingold posters, an ivory-satin gown worn by 1956 winner Hillie Merritt, and banners that hung in bars and stores promoting the competition. “The whole thing has a real Mad Men feel to it,” says Nazionale. Though it was meant to be nationwide, the contest was a huge source of hometown pride, as hotly discussed as a mayoral election. In addition to taking home a $50,000 prize, the winners were featured in ads that depicted them as wholesome girl-next-door types—preparing a rotisserie chicken, perhaps, or enjoying a day of waterskiing.

A craft-beer revival

The recent creation of the NYC Brewers Guild speaks to the growing strength of the city’s suds resurgence, which began with the now-defunct Manhattan Brewing Company in 1984. While the exhibition doesn’t directly address this recent boom, the museum does one better, offering a sampling of local varieties in a communal beer hall that serves as the show’s final stop (open Tue–Thu, Sat 2–6pm; Fri 2–8pm; Sun 2–5pm; $8 per beer). Throughout the summer, you can also check out weekly tastings (Saturdays at 2 and 4pm; $35), led by brewers from brands such as Kelso (Sat 2), Keegan Ales (June 9) and Captain Lawrence (July 7).

Those who want to delve deeper into New York brewing history, particularly in the context of its most recent act, can join the curators on July 10 for a panel discussion with Edible editor Gabrielle Langholtz and two of the city’s most treasured beer experts, Steve Hindy and Garrett Oliver—the cofounder and brewmaster, respectively, of Brooklyn Brewery. After the talk, enjoy a tasting of Brooklyn Brewery selections. Get tickets at nyhistory.org. 6:30pm; program and tasting $49, program only $24.