It’s the end of an era. After three decades of providing the world with some of the most memorable characters and stories in all of filmmaking (animated or otherwise), Japan’s legendary Studio Ghibli has ceased production, making this month’s excellent When Marnie Was There the company’s last feature film for the foreseeable future. The house that Totoro built hasn’t closed its doors for good, but when founding fathers Hayao Miyazaki (Spirited Away) and Isao Takahata (The Tale of the Princess Kaguya) both announced their retirements, it was only a matter of time before Ghibli was forced to stop and consider how to move forward.

Alas, there isn’t much reason for optimism. Marnie director Hiromasa Yonebayashi, who once represented a new generation of Ghibli, recently left the company. If his new film does prove to be Ghibli’s swansong, however, it sure makes a fond farewell. Adapted from the Joan G. Robinson novel of the same name, Marnie tells the story of a depressed 12-year-old orphan who makes an otherworldly new friend when she moves in with her aunt and uncle in Hokkaido.

Time Out New York connected with Yonebayashi over email to discuss working with Miyazaki, the end of Ghibli, and the slightly dimmed future of animation.

What was your first reaction when your producer handed you Joan G. Robinson’s novel of When Marnie Was There?

I hadn’t read the book before it was handed to me. It was a terrific, moving story, but too much of it took place inside her head for it to be suitable for animation, so I figured it was too difficult and turned it down. But the time that Anna and Marnie spend together is so sweet and fascinating that I began wanting to see what Ghibli’s terrific art department and animators could do with it, so I ultimately decided to accept.

After directing The Secret World of Arrietty from Miyazaki’s script, did you feel strongly like you had to go out on your own and make something yourself this time out?

Arrietty was a story about tiny people who borrow things in order to live, so in making the film, I figured it’s fine to borrow from the ideas and skills of my forerunners in telling the story. But I wrote the ending of the story so that the tiny people break loose from their life of borrowing and leap into the wilderness, their hearts swelling with hope. Considering that ending I wrote, I knew I had to end my life of borrowing. That was my challenge.

Studio Ghibli is known for their strong young female heroines, who are often very upbeat and energetic about life. Anna is obviously in a very different place: shy, downbeat, still developing. Was it a conscious decision on the part of the company to make a film that was about a different kind of girl?

I’m sure one of the reasons for my producer’s selection of the material was that Miyazaki was a fan of the book. At Ghibli, it’s difficult to make a film based on a book that Miyazaki isn’t a fan of. Certainly, strong and upbeat protagonists appeal to audiences more. But I think there’s value in making a film about a girl like Anna who has such negativity in her and yet manages to take a big first step. What I wanted was to portray a life-size 12-year-old girl.

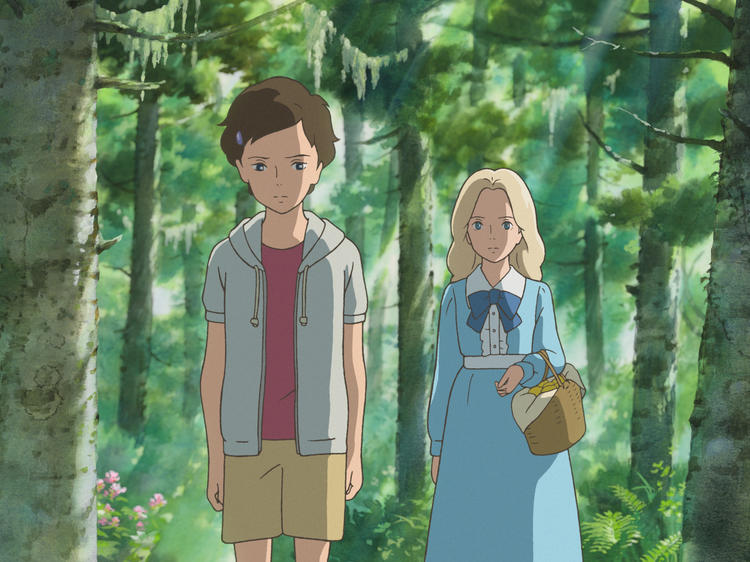

One of the first decisions made in the production was to relocate the story to Japan, and yet you decided to give Marnie blonde hair.

If we’re making this film for a Japanese audience, I figured it was only natural for it to be set in Japan. But I couldn’t picture a Japanese Marnie. She needs to be distinctive enough to stick to the viewer’s heart, and so, setting aside all the contexts, I decided to make her blonde-haired and blue-eyed. The degree to which she’s a product of Anna’s own heart is emphasized more than in the book. This way, it’s okay for Marnie to be an idealized visualization. She’s introduced at first as Anna’s ideal friend before she gradually becomes the real Marnie.

Did you channel any of the pre-existing Ghibli films for inspiration?

Arrietty was influenced by Whisper of the Heart, and I was also conscious of My Neighbor Totoro while making it. Just as viewers now look at the forest and wonder if Totoro may be out there, I wanted viewers to wonder if Arrietty may be out there somewhere in the grasses. That was my wish as I made the film. In terms of Marnie, I thought a great deal about how best to adapt the qualities of the book onto the screen. I do occasionally refer to previous Ghibli films, but I try to develop such expressions further than just using them as they are. Otherwise, viewers would be bored.

In America, it isn’t very often that we get to see animated films that are about regular people.

Dramatic expression is certainly one of animation’s strengths, but I believe hand-drawn animation is particularly effective with films like Marnie that appeal to the senses. Whereas the entire screen is in motion in a live-action film, with hand-drawn animation we get to choose what we want to bring across to the viewer. We can effectively show wind blowing during a moving scene and such. Because it’s drawn, we can draw things to be more beautiful than if they were filmed in live-action. For the scenes in which Anna and Marnie are together, I asked to have the backgrounds drawn even more beautifully.

What was the hardest detail in this film to get right?

I chose water as one of the elements to express certain things, but it was tough. How to draw it and then film it varied a lot depending on whether it’s a long shot or close-up, or depending on the camera angle, so it took a lot of time to get right, which was one of the reasons why we were behind schedule. But after Miyazaki saw the film, he told me, “I liked how the water felt like it was really there,” so I was happy about that.

Did the filmmakers at Ghibli ever watch the new computer-generated animated films from the United States? Despicable Me, How to Train Your Dragon, stuff like that?

I’ve seen How to Train Your Dragon and other Disney films. I think the filmmaking is of a very high level, and the stories are enjoyable. But I do feel like the pacing and humor are distinctly American. My personal preference is for quieter and slower films. The people around me are huge fans of American CG animation films, though.

At what point in the process did you learn that this might be the last Studio Ghibli film?

The summer before the film’s release, [Ghibli president Toshio] Suzuki told me that the production staff would be dismissed following the completion of Marnie. I felt it was an inevitable business decision that the company would need to scale down once Miyazaki decided to not make feature films anymore.

Did that knowledge make you feel a huge amount of pressure?

The company’s structure shouldn’t matter to audiences, so I continued to work as hard as I always had. We were running behind schedule, but the staff worked very hard and we managed to complete the film. I’m very grateful.

What’s your favorite Ghibli film?

I’d say My Neighbor Totoro, probably. I love how full of tenderness it is. When I saw it again recently, I was moved by how wonderfully the father handled his children.

When Marnie Was There opens Fri 22.