By the end of the 1960s, Australia—which held bragging rights to two of the world’s earliest features and first shined the spotlight on swashbuckler Errol Flynn—was long past its cinematic boom period. “There wasn’t so much a dearth of creativity,” says noted Aussie filmmaker Fred Schepisi, 73, reached by phone in New York. “There were groups all around the country cooperating with one another, trying to get things done. But opportunities were scarce.” Schepisi’s colleague, director Phillip Noyce, 62, speaking from Australia, expands on that notion: “Distribution was a problem. Theaters were owned by a number of British and American interests who only wanted to screen their own movies. And culturally, we were taught that Australians shouldn’t make films because we couldn’t do it properly—a real inferiority complex.”

That all changed in the early 1970s, when an influx of government funds and the creation of the Australian Film, Television and Radio School rippled the still waters. (“It was naught to a thousand almost overnight,” says Noyce, laughing.) The Film Society of Lincoln Center series “The Last New Wave: Celebrating the Australian Film Revival” is a stellar survey of the fruitful decade that resulted. So what, you might ask, is Michael Powell’s They’re a Weird Mob (1966; Sat 26), a fish-out-of-water comedy about an Italian immigrant’s wacky adventures Down Under, doing here? Many point to this box-office record breaker, with its affectionately satirical take on regional Aussie stereotypes, as the film that jump-started a moribund industry and gave Australians a hunger to see themselves portrayed onscreen by people in the know.

The manic energy of Powell’s film certainly informs Alvin Purple (1973; Sun 27), Tim Burstall’s crowd-pleasing sex farce about a man of plain looks but immense carnal talents. Its ribald bluntness was bracing to viewers. “Australia went from one of the most censored countries to one of the most uncensored,” says Noyce, “A lot of filmmakers took advantage of that.” And this newfound permissiveness was gleefully abused in many of the so-called “Oz-ploitation” movies, such as Bruce Beresford’s steel-tough heist flick, Money Movers (1978; Sun 27, Jan 31), with its cringe-inducing torture scene in which more than a toenail gets chopped by a pair of “nail clippers.” (Not the ones you’re thinking of.)

But it wasn’t all hedonistic good times. A seriousness of theme and purpose was also being honed in films such as Peter Weir’s hauntingly cryptic period drama Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975; Jan 31) and Noyce’s partially improvised road movie Backroads (1977; Sat 26). “It was made as a piece of agitprop,” notes the director of his unsparing look at the testy, tragic friendship between a racist drifter and a young aborigine. “And we used the energy from the actors as the catalyst for the words that were spoken. The story on the screen and off the screen naturally rolled into one.”

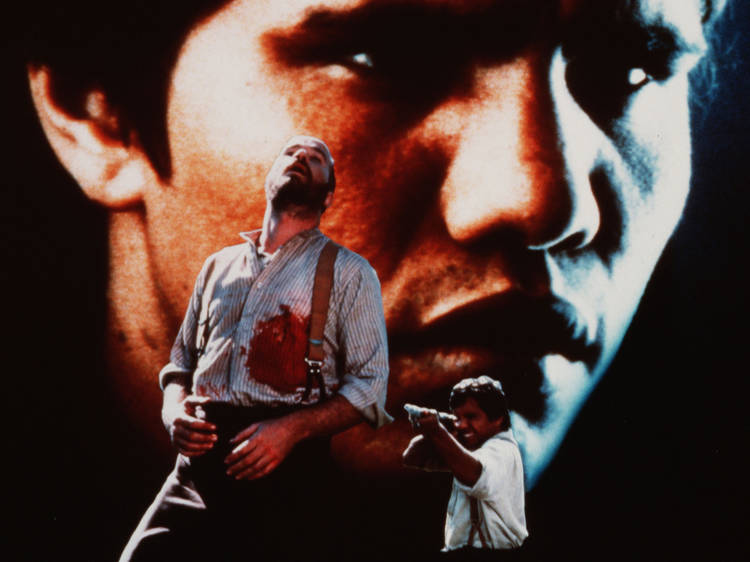

The crown jewel of this strain of filmmaking, with its evident desire to interrogate Australia’s troubled past, is surely Schepisi’s The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978; Fri 25, Mon 28), a lacerating character study of a half-white, half-aboriginal man whose thwarted attempts to succeed in turn-of-the-century Australia lead to a horrific act of violence. “The film was treated roughly at home because it dealt with issues that Australians were mostly able to avoid,” recalls Schepisi. “It was very confronting.” Blacksmith’s reception overseas—a prime berth at Cannes, a gushing review from Pauline Kael—was far better. Little wonder that, as the decade wore down and the world took more notice, many among this influential artistic generation rode the “Wave” all the way to the California coast.

“The Last New Wave: Celebrating the Australian Film Revival” runs Fri 25–Jan 31 at Film Society of Lincoln Center.

Follow Keith Uhlich on Twitter: @keithuhlich