Carolee Schneemann talks about her time with Judson Dance Theater at Danspace Project on September 21 and 22. In the program, held in conjunction with Platform 2012: Judson Now, Carolee Schneemann talks about famous works like Meat Joy, along with some of the dancers she adored: Deborah Hay, Ruth Emerson and Lucinda Childs.

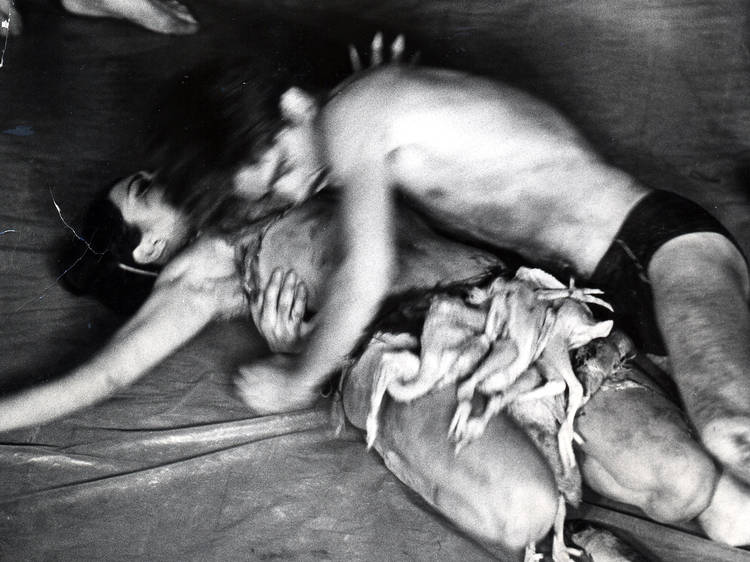

In the ’60s, Carolee Schneemann’s work evoked a similar response to what many multidisciplinary artists experience today. Was she making dances? Happenings? Paintings? (It was, of course, a combination.) On Friday 21 and Saturday 22, Platform 2012: Judson Now hosts two evenings with Schneemann, the visual artist whose groundbreaking movement works explore the body, sexuality and gender. In this Danspace Project program, Schneemann will present newly edited archival films of her works Meat Joy (from 1964, it famously involved fish, chicken and sausages), Water Light/Water Needle (originally shown at St. Mark’s Church in 1966) and Snows (an anti–Vietnam War theater piece from 1967), as well as a live performance of Lateral Splay, first performed at Judson Church in 1963. Schneemann spoke about how dance entered her life.

Time Out New York: I really enjoyed hearing you speak at Movement Research’s Judson anniversary program in July.

Carolee Schneemann: It was wonderful, wasn’t it? What is it about that space? You get the feeling of its mixed religious and cultural identity?

Time Out New York: Yes—how the two can coexist and, maybe, how art is a religious experience.

Carolee Schneemann: I think so. In a very nondenominational way, you can feel the connection there.

Time Out New York: What is Lateral Splay?

Carolee Schneemann: It’s a work based on energies from action painting in which a group of 12 to 15 participants—they might not necessarily be dancers—are trained in a set of very intense exercises to use their bodies as exploding particles. It’s a running work—as fast as possible. In one section, the knees are bent, and in another section, the arms are extended rather precariously. We practice that together and build a set of contact improvisation exercises so [the performers’] sense of self-dynamic in the space is increased, as well as their sense of contacting and locating each other, which will result in grabs and falls. It’s a good work to present in small, bursting units.

Time Out New York: Is it dangerous?

Carolee Schneemann: Yeah. But it seems more dangerous than it really is. The more you practice it, the less dangerous it is.

Time Out New York: How will you find performers for Lateral Splay?

Carolee Schneemann: The word is going out into the dance and movement communities. It’s a surprise. We all come together and see who really wants to do this and who can commit to the time and energy of it. I’m just requesting a variety of shapes, sizes, genders and races.

Time Out New York: How did you come up with the movements?

Carolee Schneemann: I am essentially a painter. And the energy of perception through a variety of forms has always triggered my sense of a whole-body musculature through the eye. How dynamic can the form be? So I was turning from elements in painting to the human body. I don’t know if that explains it, but that’s some aspect of what informs the energy. My paintings—and now my recent sculpture installations—are always all about motion and momentum. With Lateral Splay, what I want to do that I think will really be fun is to have a projection of it—so you have a virtual great big image—and then to explode that with real action. So there will be that juxtaposition. That is the second part of the evening. The first part will be showing unusual videos of mine that are involved in motion.

Time Out New York: Like what?

Carolee Schneemann: Some of the historic images that I’ve remastered: Water Light/Water Needle.

Time Out New York: What was the idea behind it?

Carolee Schneemann: It’s based on my having been in Venice and the amazing sense of merging and melting between sky and water and questioning the dimensional weight of the human body between these illusory, shifting essences and tonalities. What’s sky, what’s water and how do you carry your own gravitational weight? It’s about gravity and an aspect of almost floating the body horizontally across space. [Water Light/Water Needle was conceived as an aerial work for ropes that would be rigged across the canal at San Marco.] I had an engineer help me rig ropes—some of them were about 25 feet—across the entire space of St. Mark’s. It was in the parsonage room, not the big room. The ropes required, more than I ever thought, a great deal of calluses and muscle memory; initially, it was [based on] a series of drawings of bodies almost floating across space on the ropes, and the ropes were at three levels and crisscrossed—some were very high, some were medium height and some were rather low. The instructions for the work have to do with the motion between the ropes; also, every time you come up on another person, your intention has to change and absorb theirs. We did it outside in New Jersey at the old estate of the Havemeyer’s, and that was very interesting. I love to perform outside. I started as a landscape painter, so “outside” is an affinity of potentiality. It was beautiful, it felt so good. And that footage has not been properly edited until this year, so I’ll show that.

Time Out New York: And you’re also showing a reedited version of Meat Joy?

Carolee Schneemann: Yes. Meat Joy was a vision of sensuous interaction that I conceived of for an invitation to perform in Paris, for Jean-Jacques Lebel’s experiments in the First Festival of Free Expression. Once I had that invitation, I began imagining a very sensuous interaction between the participants and visceral materials: It would be fish and chickens and sausages. So I created a whole score of what I would call movement parameters; there would be movement parameters within which improvisation and unexpected aspects would develop. There was a corps of eight performers and what I call the “director/reality” figure. The woman who kept the clock and could time sequences and who would, at the right point—after there was a movement collapse from an impossible circle movement—introduce the trays of chicken, fishes and sausages.

Time Out New York: Why did you want to use the food as your material?

Carolee Schneemann: They’re very basic to still life. They’re visceral. In our tradition, they’re always suggestive of luscious surface, domestic organization—in the old Dutch paintings, there are piles of fish being brought in from nets, and then they go to these very appealing tables with fruits, vegetables, fish and chicken. I wanted to activate an art-historical iconography that’s wet and weighty and smelly and bring it into my extension of painting traditions.

Time Out New York: I wish you could bring that back. I suppose St. Mark’s Church would be against that.

Carolee Schneemann: [Laughs] The [Judson] minister at the time, Howard Moody, was so wonderful. Meat Joy was performed in the center of Judson church, and the whole sanctuary really stunk of the fish, but Pastor Moody was so gracious. He built a sermon around it.

Time Out New York: You started making performance works well before the first performance of Judson Dance Theater, right?

Carolee Schneemann: Yes. The first performance I did was in Sidney, Illinois, outside of Champaign-Urbana where [composer] Jim Tenney and I had graduate fellowships. A tornado came through—we lived in a really fragile little shack in the only woods that we could find within 20 miles of the university, and so trees came down and the little stream bed flooded. One of the trees crashed down through our kitchen and our landlord was 80 years old. We knew this was a disaster, and we had no idea what to do, but my cat Kitch studied this tree in the sink in the smashed window and immediately saw it as a doorway: a magical entrance-exit. She walked along the branch of the tree from the sink outside to the field, and I said, That’s what I want to do. I want to have that inside-outside dynamic. So smooth and connective. So the first performative work was to invite people, friends from the university, and give them cards to be within the altered landscape, to be in the mud, to be in the water, crawl under the trees and over the trees. I didn’t know exactly what I was doing, but I was intensifying the process of painting by putting the body where the brush had been. It’s something like that.

Time Out New York: Do you see bodies as colors?

Carolee Schneemann: I did when I worked with the Judson group. Lucinda Childs was yellow and golden, and Deborah Hay was sort of rosy and red tones, and Ruth Emerson was my blue. But the thing that was very unexpected was that some of my colors wouldn’t turn up when I needed them. They were not available. They had another job. [Laughs] I can’t go on without the yellow! It was funny. I also had very vivid drawings and sensations about aspects of the movement each of those bodies seemed to inhabit.

Time Out New York: In what way in terms of someone like Lucinda Childs?

Carolee Schneemann: With Lucinda, I always created something very formally structured and unified. Deborah was sort of my alter ego because I didn’t do performance yet, so she had more wild, sexy contact actions happening. For Ruth Emerson, with those incredible legs, I always conceived of works having to do with elongation in space. And, of course, Meat Joy evolved out of the earlier Judson pieces. But I was still painting and doing installation work at the same time. Then I began to use my own body in Eye Body, the visual sequence of self-transformations for camera.

Time Out New York: When did you first start using nude bodies?

Carolee Schneemann: I used my nude body in Eye Body in ’63 [in which Schneemann merged her own body with the environment of her painting/constructions]. That was part of physicalizing a room that was energized and very free in terms of, again, addressing this history of the nude and revitalizing it. I might as well mention this—in these years, one of my jobs was as an artist’s model. I wanted to see if I could really interfere, in my literal way, with that tradition of the passive nude and the painter, always a guy—and always an older guy—telling the students how to look. So that was one contrary influence. Also Pop Art where the women were so mechanized. That influenced my making Fuses, the heterosexual erotic film [of collaged and painted sequences of lovemaking between herself and James Tenney]. We were definitely naked. [Laughs] Part of the presumption of addressing those bodies came from my cat Kitch. She had such a shameless appreciation for our being lovers. And she would always come close and be very discreet—we would never see her staring at us unless we suddenly opened our eyes.

Time Out New York: Why did you start working with dancers? Was it in reaction to something you saw? Or was it really a conscious way to extend your painting?

Carolee Schneemann: Yes, and I guess I always had a lot of dance feeling personally. I admired so much what they could make and do, and I felt a bit like an interloper, but I wanted to try and put some of the kinetic drawings I was making into actual bodies. I guess I had already been in [Claes] Oldenburg’s Store [Days], and that was a huge influence: It was being inside someone’s visionary material. It was so wonderful at how it was coming from a painterly, almost deformation, of potential structure. It was a sense at the time of an exploded canvas. Or what I would call a sensory arena. To go into real time and dimensional space.

Time Out New York: What did that show you about your work and your ideas?

Carolee Schneemann: It just confirmed that one could go further with that and use more varied aspects of space and material. But a lot of it is very instinctual: Up to and Including Her Limits [1973–76] starts by watching my friend, a tree surgeon, hanging his harness and cutting the tree limbs. [In this reaction to Jackson Pollock’s painting process, Schneemann is suspended in a tree surgeon’s harness on a three-quarter-inch Manila rope that she raises or lowers manually in order to draw.] Because of Water Light/Water Needle, I recognized the three-quarter-inch Manila rope and thought, I can work with that. And the harness is a very interesting, also antigravitational source of suspension and momentum. So even if it’s intuition, intuition is everything that you know and have ever done. It’s not blind, but it doesn’t have a predetermination.

Time Out New York: Was it fairly easy to find willing dancers and willing bodies at Judson?

Carolee Schneemann: Yes! Because we were all in the initial group and the premise was to help each other and be available. And I was thrilled to be in the running piece or the standing-and-chanting piece. We all wanted to give whatever somebody might need. For Meat Joy, the performers were all, with maybe one exception, untrained people that I found in bars and on street corners.

Time Out New York: Why did you want them untrained?

Carolee Schneemann: I wanted to escape the dancer’s sense of physical construction and predictive motion and momentum. I wanted people that could just fling themselves into space and feel an adventurous confidence, and I had reached a point with trained dancers where that was too much of an imposition coming from me. I wasn’t a dancer, and some of them felt that the work was not safe for them or too messy. They’re highly trained to break the forms that they’d been trained in. And I was coming in from a different direction. It was painterly and gestural. In the ’60s, none of us knew that this would matter to anybody very much. [Laughs] I think you never know. You kind of know, but it’s so uncertain. There’s a crucial transformation underway. Will it enlarge? It certainly has more than enlarged. The concept of performance is viral. It can be anything, anything.

Time Out New York: What do you think of that?

Carolee Schneemann: Well, I can’t say because anything that I say becomes exaggerated in its reception. I guess everyone should be encouraged. [Laughs slyly]

Time Out New York: Had you had any training in dance yourself?

Carolee Schneemann: Not really, but I always danced before I painted to Bach or to rock & roll to really feel energized. It was sort of a private, secret thing. I’d close the door, put the music on and go to the studio to paint. I kind of still do it.

Time Out New York: Why is Judson Church, as a place, special to you?

Carolee Schneemann: Well, it’s exquisite. The proportion, the architecture—it’s a beautiful, almost Romanesque, structure and it has such enriched memories. I’m sure it’s like this for most dancers and performers: When you inhabit and physicalize a space and bring something to life in it, it stays with you—it’s almost like a habitation. So I have that with every place where I was able to realize a very strong work. I think especially Judson, because the proportion is so beautiful. No matter how long I’ve been away, it’s a home base.

Time Out New York: Do you consider yourself to be a choreographer?

Carolee Schneemann: Sure. But with a parenthetical: a choreographer as extending principals of media. I could say that Robert Whitman is a choreographer; Oldenburg, for sure. Maybe Red Grooms. Or let’s say there are choreographic developments or aspects, but they’re not choreographers the way a choreographer would justifiably define herself or himself.

Time Out New York: Could you describe your choreographic process?

Carolee Schneemann: They all start with highly energized drawings of bodies in action or activities, and then if the drawings seemed present or intense enough, I would bring them to the Judson group and see what might come of it. They would study the drawings, and I would begin to choreograph the movements they adapted from the drawings. I would work with duration, position and relationship to the space, which wasn’t always the dancer’s concern at all. For instance, in the Judson gym, we had two basketball hoops and I thought they functioned very strongly as dimensional material—almost as a head and shoulders hanging up there in space—so I was concerned with how they related to our movements, as well as the radiators—things like that. The dancers didn’t pay those any mind. Whereas wherever painters were doing happenings or events, the whole space was seized with energy.

Time Out New York: What are you working on now?

Carolee Schneemann: I’m doing kinetic sculpture within projection. I saw these shapes—I call them flange—and they’re three and a half or four feet high. I’m not sure what they resemble; maybe wings or leaves. And then I build them out of wax and they’re poured in a foundry. They’re burnt into aluminum shapes, so each original is destroyed and these aluminum sculptures are motorized, with the motor in a computer chip turning them. Three or four of them move from the same base and precariously twist backward or forward or go slowly around and they extend to the wall on an extended kind of arm. They move at 6 RPM, and they’re moving within a projection of a fire that burnt their shapes into the aluminum, so they’re dynamic and they’re big. You walk right into it.

Carolee Schneemann is at Danspace Project at St. Mark’s Church in-the-Bowery Sept 21 and 22.

You might also like

SAB dancers explore Balanchine's Serenade

Jennifer Howard talks about her dance career

Ralph Lemon, the curator of an upcoming dance series at MoMA, discusses his Parallels marathon