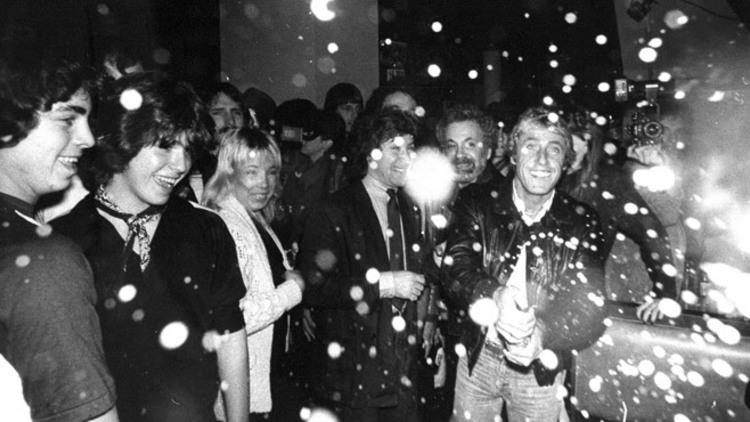

The Loft

This was the inspiration for pretty much every DJ-driven party that followed, and many credit it as being the birthplace of modern nightlife. But the Loft, famed for its transcendence-through-music ethos, came into being in humble fashion in 1970—as a rent party for David Mancuso’s Broadway loft. Eventually, through Mancuso’s unparalleled music selection (his reverence for the art form is such that he didn’t mix the records, preferring to let them play from start to finish without interruption) and the love and togetherness that defined the Loft’s vibe, the soiree entered the history books as one of the best parties ever. More than four decades later, Mancuso’s still at it, tossing the occasional Loft in the East Village (as well as London and Japan), where revelers who have been with him since the beginning dance next to younger folks hungry for some gravitas in their nightlife.

Colleen “DJ Cosmo” Murphy, DJ and coproducer of the David Mancuso Presents the Loft compilations: “The reason the Loft parties have lasted so long is that they focus on the fundamentals of a great party, but they execute them in the highest-quality way. For instance, you have the highest-end sound system for a party in the world. It enables people to hear music in the clearest way possible, and they can immerse themselves in the music in a deeper way. And there’s the music: One of the things that David is always trying to do at the Loft is to enable people to hear music in the way that the artist intended. The point is to have a deep emotional experience with the music, as opposed to having DJs’ egos involved. That’s why there’s no mixing. You really have to choose quality songs that are great from beginning to end and that tell a story in themselves. And then there’s the atmosphere, which really allows people to let it all hang out. It’s kind of a hippie vibe, where people from all different parts of society can hang out. One of the reasons David started the party was that he was really interested in civil rights; it was really about mixing different groups of people: race, sexuality, economic class—it doesn’t matter. For a lot of parties, it’s all about commerce—but the Loft has a warm, loving atmosphere. That’s why the Loft is still here.”