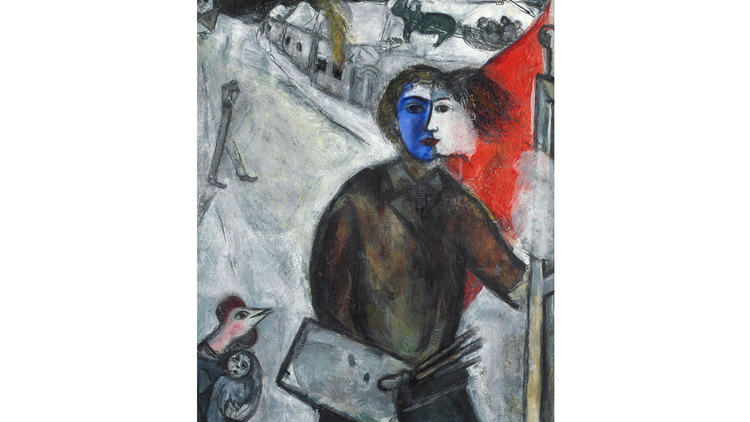

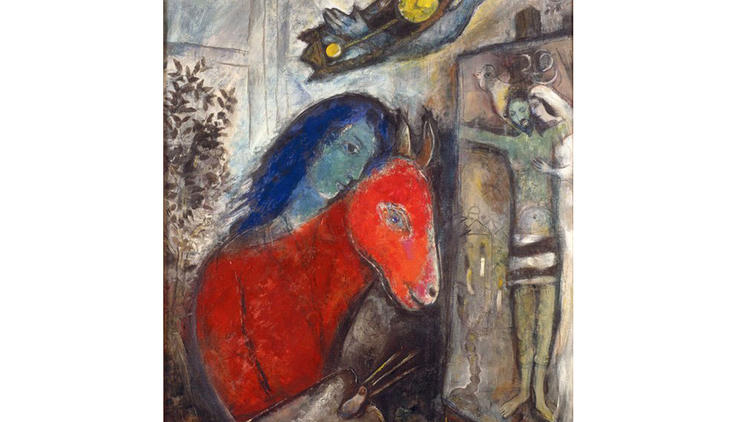

Marc Chagall (1887–1985) is best known for a certain, well, shtick: a Fiddler on the Roof vision of shtetl life as a mysticism-infused idyll, bathed in prismatic hues and filled with levitating animals and people. But Chagall was Jewish, after all, and more than a little aware of the precarious position of Europe’s Jews in the years before World War II. Under Stalin, the Russian Revolution had turned against them, while in Germany, Hitler’s rise set the stage for the Holocaust—precipitating Chagall’s escape to New York in 1941. Just how these events impacted his art is the subject of this survey of works from the 1930s and 1940s.

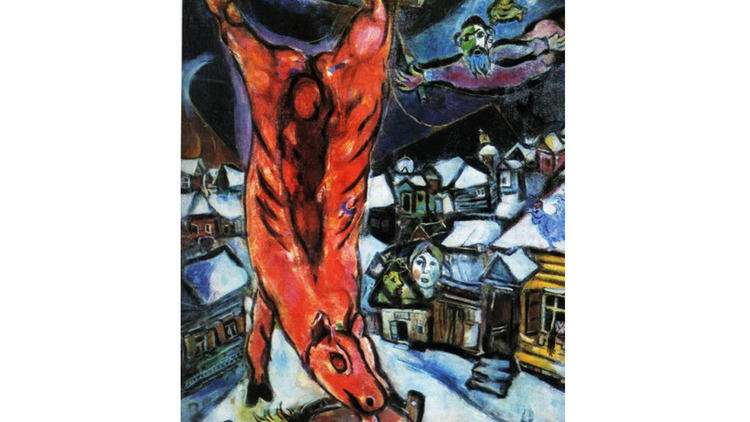

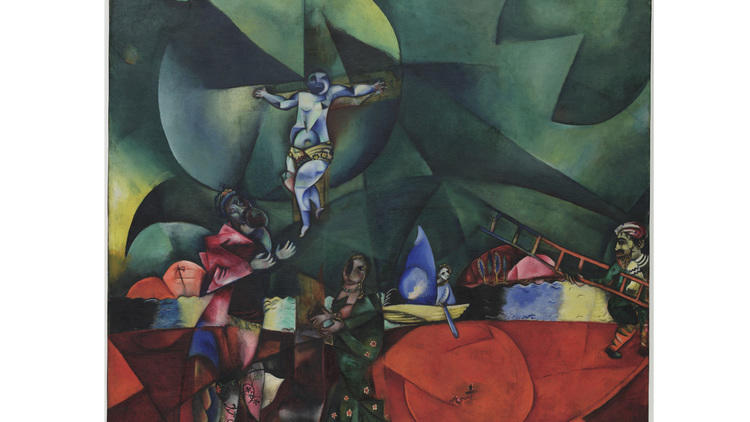

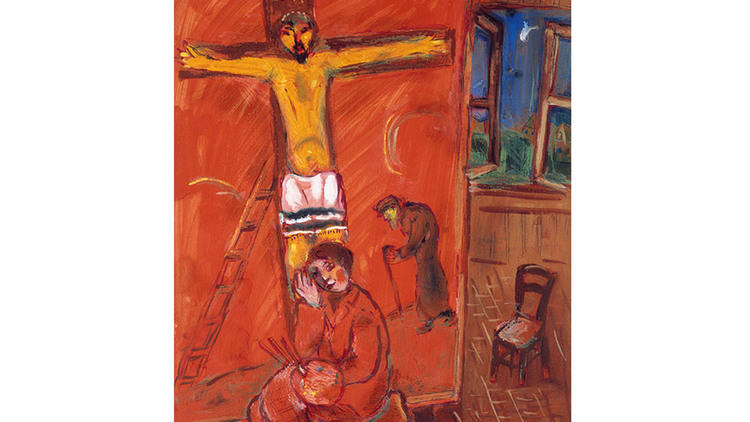

With the walls painted a dark blue and punctured by spotlights, the pieces appear to swim out of the gloom, as if awakened from uneasy dreams (to paraphrase Kafka). While it’s odd to think of Chagall in a grim context, the exhibit demonstrates that he often depicted himself in a tortured vein: Crucifixes are a recurring motif, sometimes with the artist nailed to them, sometimes with the original occupant presented not as the Christ, but as the symbol of all afflicted Jews, including the artist.

As much as this Jesus fixation is something of a revelation, however, the emotional core of the show rests on Chagall’s devastation over the sudden death of his beloved wife, Bella, in 1944. This sorrow would color his output until well after the war’s end. The fantastical nature of Chagall art makes it easy to forget that his work was autobiographical; in that sense, the show adds some necessarily darker tones to our view of him.—Howard Halle