Darja Bajagic

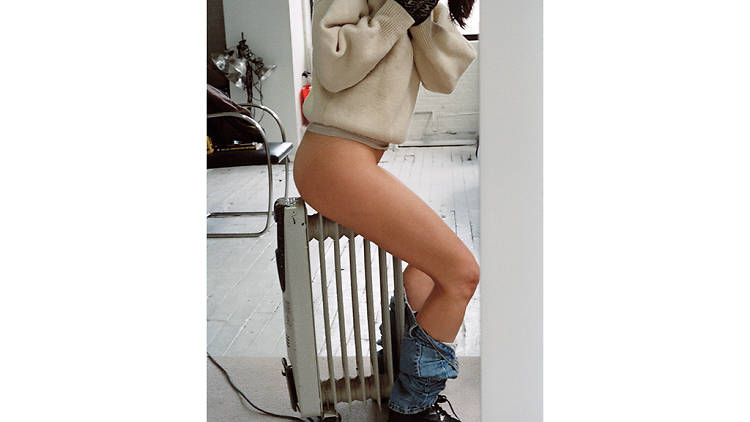

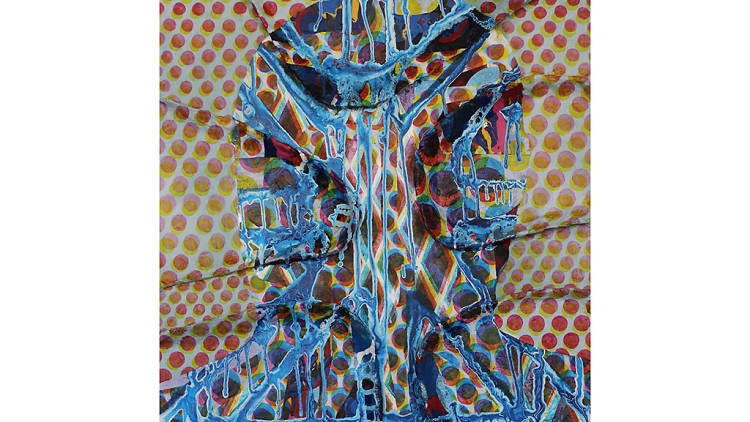

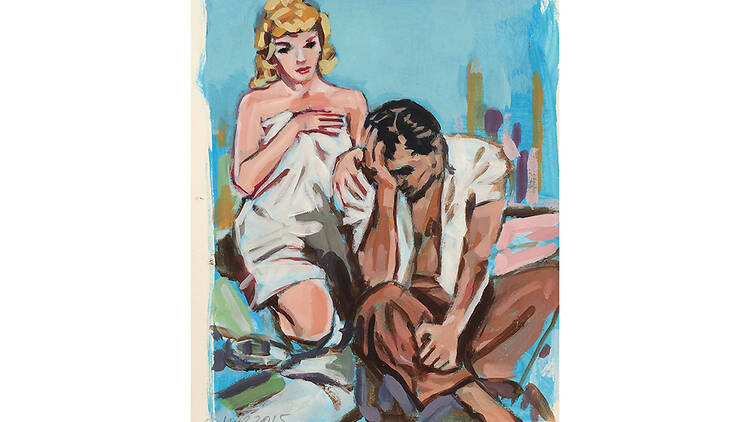

Born in the former Yugoslavian state of Montenegro, 25-year-old New York artist Darja Bajagic is a recent Yale MFA graduate, but she’s already caused controversy. Even while she was still in school, Bajagic’s work was so unnerving that the head of the department, former MoMA curator Robert Storr, questioned her sanity. But while her work may be outré, there’s nothing unhinged about it. Dwelling on the (very) dark side of human nature, Bajagic’s collages, drawings, paintings videos and photographic pieces (some of them sculptural in form) draw upon a disturbing wellspring of pornographic imagery and serial-killer narratives. She depicts the way society reduces women to sexual objects and targets of violence. That women themselves are blamed for this state of affairs represents the real horror behind Bajagic’s amalgam of Goth aesthetics and feminist critique.

Darja Bajagić, Puddles of Blood - Don’t Tame Your Soul, 2015

Photograph: Pierre Antoine; courtesy the artist