The Barbican Centre lures fans of serious culture into a labyrinthine arts complex, part of a vast concrete estate that also includes 2,000 highly coveted flats and innumerable concrete walkways. It's a prime example of brutalist architecture, softened a little by time and some rectangular ponds housing friendly resident ducks.

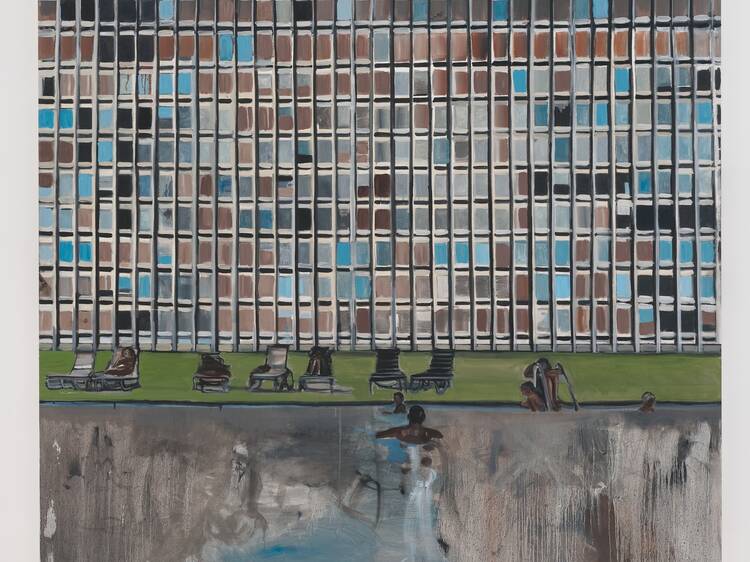

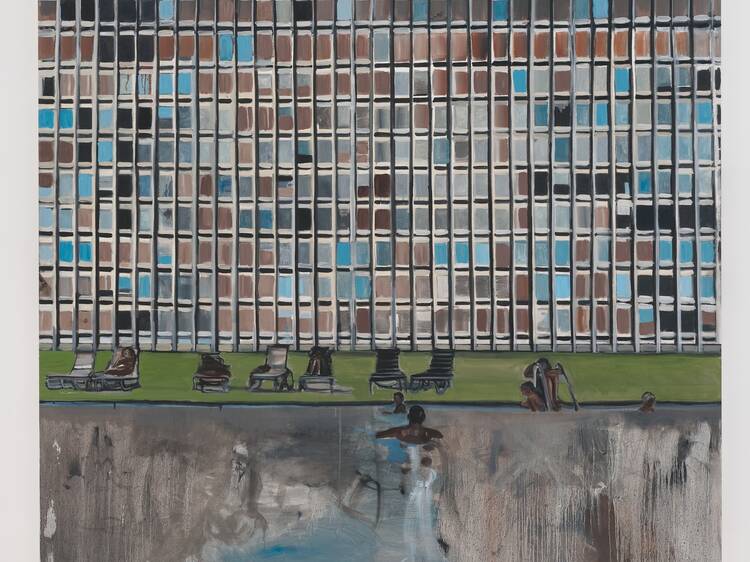

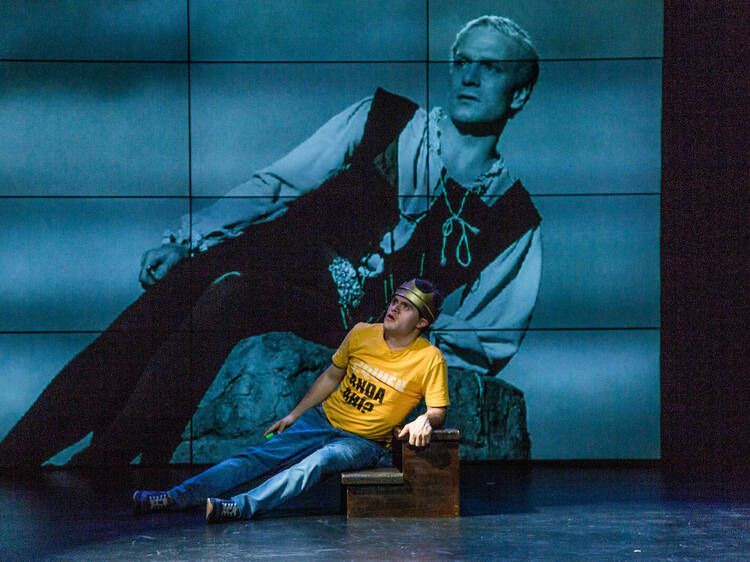

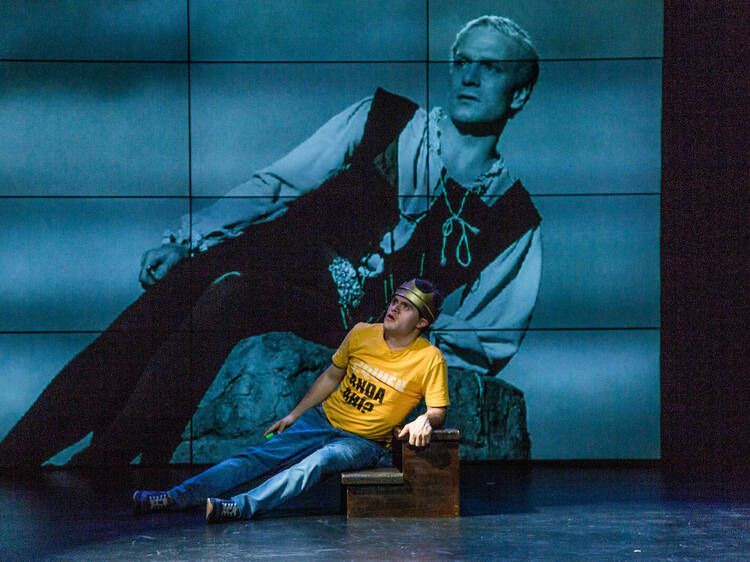

The focus is on world-class arts programming, taking in pretty much every imaginable genre. At the core of the music roster, performing 90 concerts a year, is the London Symphony Orchestra (LSO), which revels in the immaculately tuned acoustics of the Barbican's concert hall. The art gallery on the third floor stages exhibitions on design, architecture and pop culture, while on the ground floor, the Curve is a free exhibition space for specially commissioned works and contemporary art. The Royal Shakespeare Company stages its London seasons here, alongside the annual BITE programme (Barbican International Theatre Events), which cherry-picks exciting and eclectic theatre companies from around the globe. There's a similarly international offering of ballet and contemporary dance shows. And there's also a cinema, with a sophisticated programme that puts on regular film festivals based around far-flung countries or undersung directors.

As if that wasn't enough, the Barbican Centre is also home to three restaurants, a public library, and some practice pianos. This cultural smorgasbord is all funded and managed by the City of London Corporation, which sends some of the finance industry's considerable profits its way. It's been in operation since 1982; its uncompromising brutalist aesthetic and sometimes hard-to-navigate, multi-level structure were initially controversial, but it's getting increasingly popular with architecture fans and Instagrammers alike.

As the UK's leading international arts centre, this is the place to get cultured.

The huge, succulent-filled Barbican conservatory is a must-see on your London bucket list. It’s one of the biggest greenhouses in London, second only to Kew Gardens and houses 2,000 plant species, including towering palms and ferns, across an extensive series of concrete terraces and beds. There are even koi carp and terrapins. The atmosphere is almost post-apocalyptically peaceful. It’s open on Sunday and bank holiday Monday afternoons, as well as selected Saturdays. You can even book in for an afternoon tea among the plants.

Mon-Friday 8am–11pm, Sat-Sun 9am–11pm

Free entry, some events and exhibitions are ticketed.

If I had a pound for every time I’ve tried and failed to find the entrance to the Barbican Centre among its maze of concrete walkways… If you don’t want to risk being late for the performance you’re seeing, look up the entrance you need in advance. Trust me.

Find more culture in London and discover our guide to the very best things to do in London.

Discover Time Out original video