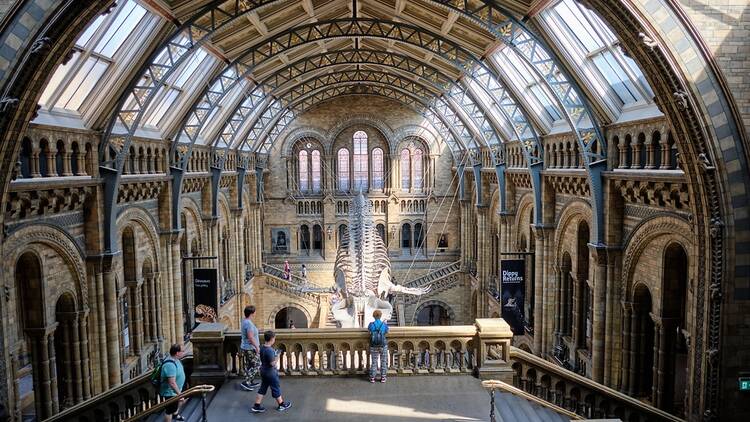

ALSO SEE Animal, vegetable or mineral: from dinosaurs onwards, it’s all here.

Ten weird London museum exhibits

ALSO SEE Animal, vegetable or mineral: from dinosaurs onwards, it’s all here.

The Science Museum is home to the first steam engine, first computer and first samples of penicillin – great objects that could be classified as some of the most important exhibits in any museum in the world. Easily overlooked among these giants of science is this fascinating and beautiful curio. ‘Palace of Pills’ was built in 1980 out of medicine bottles and syringes by artists Peter Dunn and Loraine Leeson. It was used as a model for a poster campaign by the East London Health Project, which was pro NHS and anti big pharma. The pill palace was a warning about the commercialisation of medicine and the power of multinational drug companies – things that London campaigners are still getting exercised about today.

ALSO SEE Progress, industry and things that go ‘bang’ when you pull a lever.

ALSO SEE The best of British art from 1500 to the Turner Prize.

ALSO SEE As new exhibition ‘The Story of Music Hall’ shows, highbrow and lowbrow art, design and fashion meet at the V&A.

ALSO SEE A huge collection of works by masters as Van Gogh, Rembrandt and Titian.

ALSO SEE Mad historical curios and cutting-edge medical science, like the entire archive of DNA and modern genetics, now freely available at www.wellcomelibrary.org.

ALSO SEE Seven million artefacts of plague, fire and empire in the city’s definitive memory box.

ALSO SEE Cool original tube art and all things London transport.

ALSO SEE Millions of other objects from all over the world and the British Museum's soaring Norman Foster glass dome, under which they serve a very decent coffee. British Museum

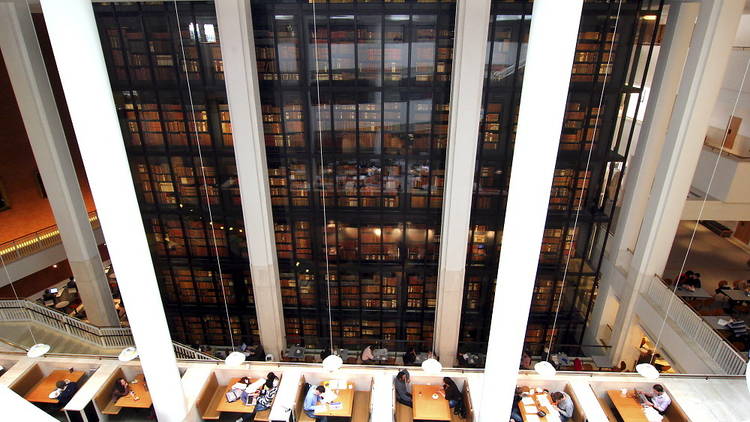

ALSO SEE Pretty much every book that's printed in Britain, if you join the British Library.

Find more great things to do in London

Discover Time Out original video