Danny Boyle’s ‘Frankenstein’ is already a monster hit for the National Theatre. Does it live up to its billing? The answer is an almighty ‘yes’.

This ‘Frankenstein’ belongs to the monster – or ‘the Creature’, as it’s re-christened in Nick Dear’s script – which is, by the way, highly sensitive to the currents of revolution, reason, and Romantic death-driven art that first animated Shelley’s Gothic vision. Boyle’s production begins with the Creature’s unnatural birth from what could be described as a Da Vinci pod: a man-sized vellum-coloured circle, which ejects a scarred and writhing life-form, like a parody of Leonardo’s ideal diagram.

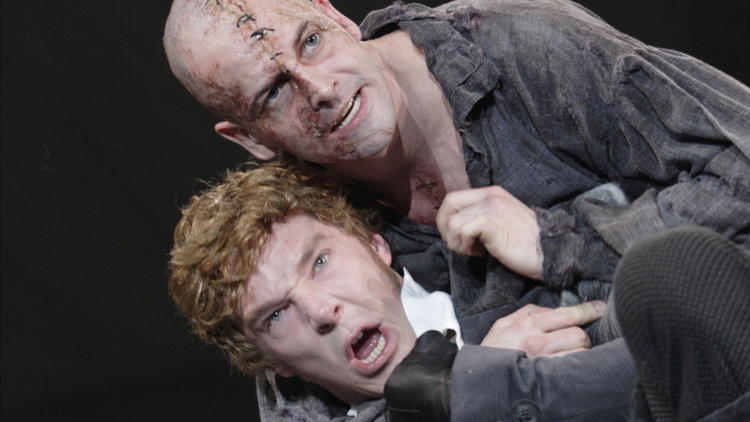

This birth scene is an extraordinary challenge for an actor: 15 minutes of fully naked jerks and rictus-mouthed pangs, under the harsh pulses of light that thrum through the brilliant rack of bulbs and alembics that roof the auditorium. Both Benedict Cumberbatch and Jonny Lee Miller, who alternate the roles of Frankenstein and his creation, deserve respect (if you’re in the front row, prepare for an eyeful), but the more muscular Miller is a revelation as the Creature. He brings a powerful brutish innocence to this man-made baby, rejected at birth, and makes his many acts of destruction, such as torching the kind old blind buffer who teaches him to read using ‘Paradise Lost’, seem elemental and therefore less irredeemable.

Cumberbatch is camper, funnier and nastier in the monster’s role. But you feel more for Miller’s Caliban-like Creature. And Cumberbatch – as fans of the Beeb’s ‘Sherlock’ will attest – has a sadistic flair when it comes to playing a semi-autistic genius with a chip of ice at his heart. The dynamic of the duo works best with Miller providing the muscle and the pathos, Cumberbatch the flamboyant, cerebral chill.

The strength and weakness of Dear’s adaptation is how faithful it is to Shelley’s novel. ‘Frankenstein’ might have been more pertinent updated to our own Cyborg era – Underworld’s music, which sounds like a dance of heavy machinery in the sinister bits and synthesised optimism when the Creature gambols on the grass on his first day, underscores the possibility.

The production might have been more claustrophobic and scary if Dear had imposed some unities of place and time – instead, months are telescoped into minutes as we follow Shelley’s monster across Europe. But the payoff is an unforgettable showdown in the arctic ice, where the murderous, rejected Creature cuts a Beckettian caper at the end of the world and teaches its cold Creator something about the essence of love.

Boyle – who cut his creative teeth in the theatre – does a film-tastic job of whisking us from location to location on the Olivier’s revolving stage. Allegory meets nightmare, in the spectacular steampunk train that comes whistling and sparking towards the audience; the wedding night murder in Frankenstein’s whiter-than-white family house, with its Enlightened proportions; and in the figure of the Creature’s bride, a goddess sutured together from corpses, whose docile grace and downcast eyes are modelled on Botticelli’s 'Birth of Venus'. In true Gothic spirit, it shows how the God-like and monstrous capacities of man are conjoined – and that either can be master of the other.

It’s not all superlative. The line between allegorical simplicity and clunkingly clichéd lines is always narrow and often crossed. The bit parts are broadly written and overplayed (with the honourable exception of Karl Johnson as the Creature’s teacher). Naomie Harris endeavours to be luminous as Frankenstein’s underwritten fiancée. George Harris fails to make any emotional sense as Frankenstein’s father. But these elements are not, fundamentally, what so many people have paid to see.