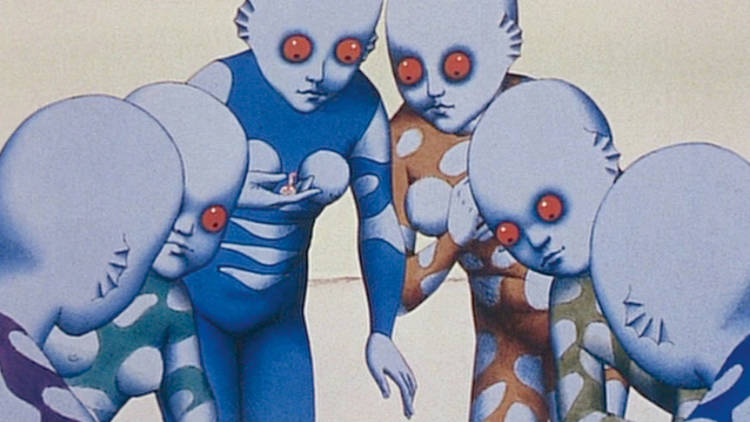

Miyazaki proves he has the heart of a child, the eye of a painter and the soul of a poet.

Director: Hayao Miyazaki

Best quote: “Trees and people used to be good friends.”

Defining moment: The first appearance of the roving cat-bus will have viewers of all ages gasping in delight.

Some filmmakers build their great artworks with blood, sweat and toil. Japanese master Hayao Miyazaki seems to sprout his from seeds, planting them in good earth and patiently watering them until they burst into bloom. My Neighbor Totoro is the gentlest, most unassuming film on this list, a tale of inquisitive children, mischievous dust fairies, magical trees and shy sylvan creatures. But in its own quietly remarkable way, it’s also one of the richest and most overwhelming.

This is a story whose roots go deep: into Japanese tradition and culture, into its creator’s personal past, into a collective childhood filled with tales of mystery and a love of all things that grow. There is darkness at the film’s heart—the fear of losing a parent, the loneliness and frustration of childhood—but its touch is gossamer-light, delighting in simple pleasures like raindrops on an umbrella, dust motes drifting in the sun and midnight dances in the garden. The visual style is unmistakably Japanese (unadorned and artful) and the theme song is so sugary-chirrupy-sweet that it’s impossible to dislodge once heard. But the cumulative effect is unique and utterly all-encompassing, returning us to a world we have all, at one time, lived in—and perhaps will again.—Tom Huddleston