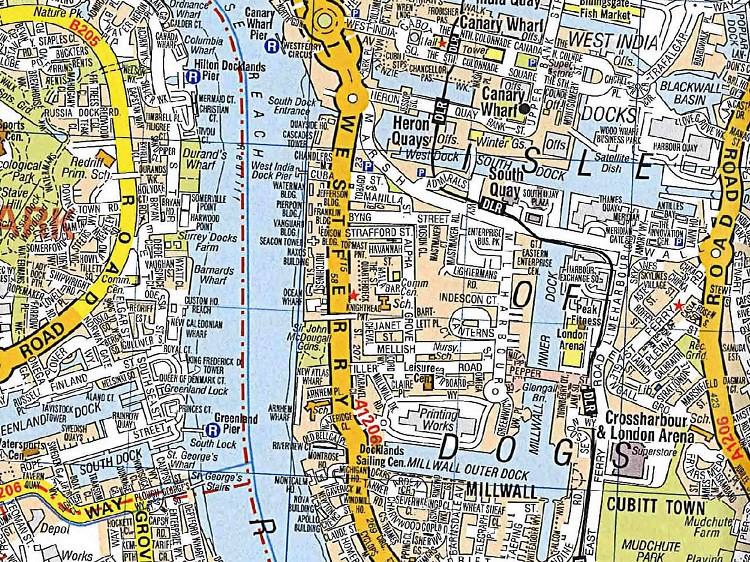

London Underground’s graphic identity 1908-1920s

The panel’s verdict: ‘London Underground’s early corporate identity was masterminded by London Transport’s Frank Pick. The wonder is that it has survived and looks as good as ever.’

Simon Esterson, creative director of Eye Magazine