Pop art legend Richard Hamilton is the flavour of February with a retrospective at Tate Modern and a show at the ICA. Bit shaky on your art history? Here's what to say on your date at the Tate

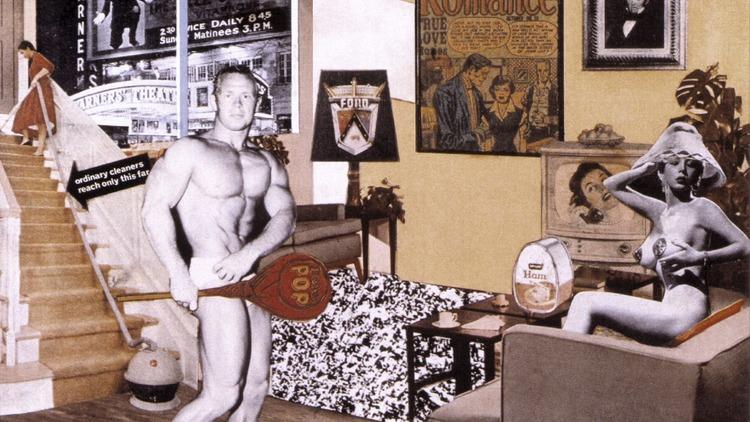

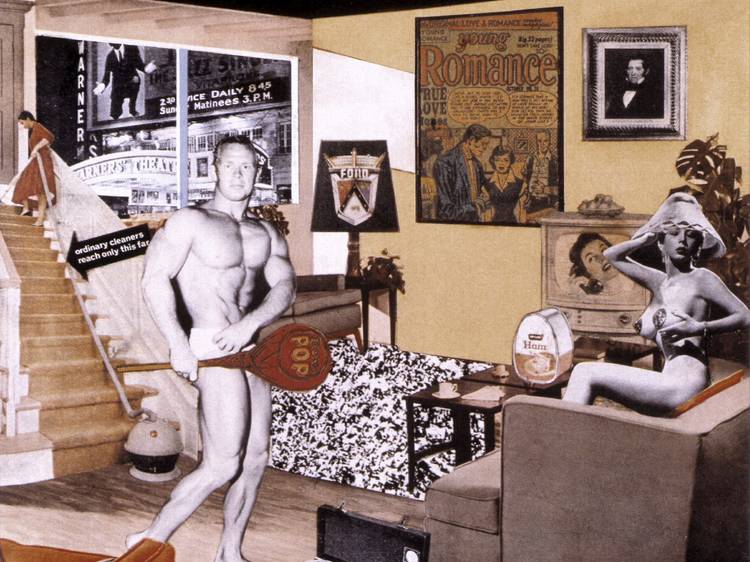

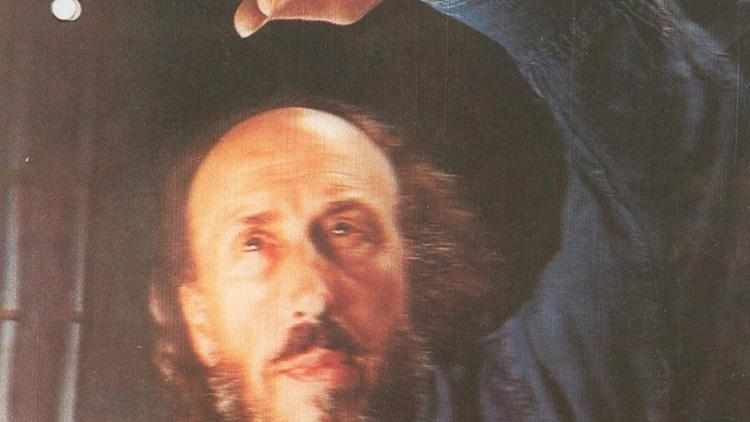

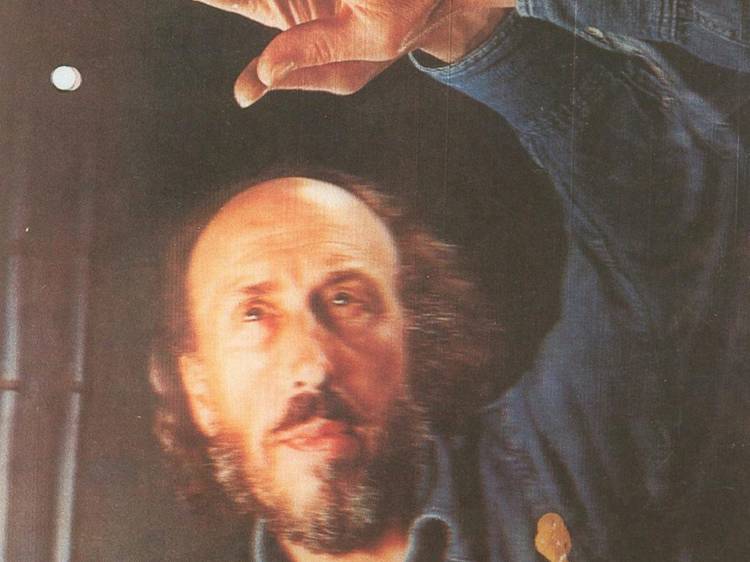

Having pipped the likes of Andy Warhol to the post in 1954 with his proto-pop collage 'Just What Is It That Makes Today's Homes So Different, So Appealing?' Richard Hamilton could have rested on his laurels, happy in the knowledge that his place in history was assured. But Hamilton, whose death in 2011 aged 89 robbed us of our most forward-thinking artist, wanted more than to bathe in history's glow: he wanted to mine its most intense images - like Mick Jagger and the art dealer Robert Fraser handcuffed together after a drugs bust in 'Swingeing London 67' (1968), or IRA prisoner Hugh Rooney standing beside his shit-daubed walls in 'The Citizen' - and reflect them back to us as cool, often highly satirical artworks. As much as he celebrated the fast pace and seductive lustre of the times in paintings like the sexy semi-abstraction 'Hommage à Chrysler Corp' (1957), he looked beyond flashy surfaces, fast cars and smooth celebs to examine how those images entered our consciousness via newspapers or were beamed into our living rooms on TV.

'He looked beyond flashy surfaces, fast cars and smooth celebs'

If he lacks the wider fame of twentieth-century artists like Francis Bacon and Henry Moore, it's probably down to his desire to keep ahead of the game by changing it. Mark Godfrey, curator of Tate Modern's Hamilton retrospective, which opens this week, says that Hamilton's slipperiness was a deliberate strategy. 'I think he is hard to pin down because he wanted to change styles and approaches between every group of works. You'll find that throughout the exhibition - works that deal with the Vietnam War at the same time as works that deal with fashion models in Vogue.'

Hamilton took his cue from chess-playing dada supremo and pisstaking purveyor of the urinal-as-artwork, Marcel Duchamp. Like Duchamp, Hamilton seized on readymade objects, using images of freshly-minted consumer desirables like Braun toasters but replacing the logo with his own name. 'I don't think he's mocking Braun in anyway,' says Godfrey. 'But I think he's playing around with the idea of the artist as a single author, associated with a style of brushstroke, and being tongue in cheek about the idea of the artist's signature. For me, the key question is how Hamilton managed to be sceptical about values of consumer culture while at the same time really appreciative of the objects it created.'

Obsessed with how pictures are selected, edited and served up to us, Hamilton was the ultimate history painter for the modern, media-saturated age. 'He was really interested in the transmission of images through technology,' says Godfrey. It's plain to see in 'Kent State' (1970), in which an image of a student shot during a peaceful anti-Vietman War demonstration is framed by the curve of a TV screen. 'Nowadays, he'd be dealing with the idea of watching TV on your smartphone on the way to work.'

Hamilton shows us a world where the roles of subject, consumer and sometimes even patient overlap. This makes for a chilling vision in his installation 'The Treatment Room' (1983-84), in which Margaret Thatcher delivers a speech via a video monitor placed above a bed in a hospital room. For Hamilton, the particular speech was important. 'It was the first party political broadcast for which a British politician hired an image consultant,' says Godfrey. 'I think he intuited that this was a shift in British politics, away from a moment in the 1970s when British politicians would tell you what their policies were, to a moment where politicians create an image, and that becomes more important than what is being said.'

'There's a materiality that people can enjoy'

It's not all screens and machines, though. 'There's a materiality that people can really enjoy,' says Godfrey. 'The way he uses oil paint, his range of touches, drips and strokes, is beautiful.'

And if you like a chuckle with your conceptualism, the Tate's show includes a string of works from what Hamilton called his 'scatalogical period' from the early 1970s. These are a series of paintings and prints of schmaltzy sunsets, pastel landscapes and saccharine still lifes to which the artist has added loo rolls and neat extrusions of poo. Richard Hamilton: exquisitely aware of the sleek, sanitised, mediated world in which we live, but never afraid to cause a stink.