Our slideshow shows the original paintings that inspired each of Landy's kinetic sculptures.

Sassetta

The Stigmatisation of Saint Francis

1437-44

© The National Gallery, London

-----------

Michael Landy

Saint Francis Lucky Dip, 2013

Mixed media 284 x 160 x 343 cm

© Michael Landy, courtesy of the Thomas Dane Gallery, London / Photo: The National Gallery, London

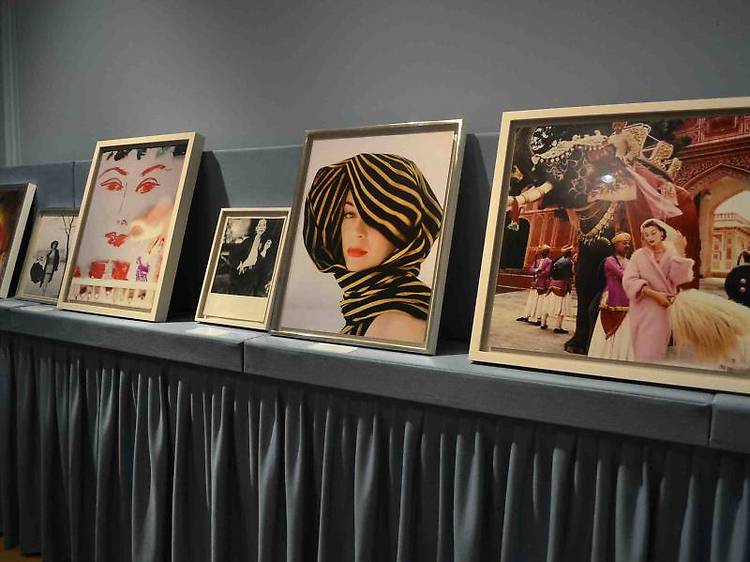

For the past three years, Michael Landy, known for destroying all his worldly possessions in 2001, has immersed himself as the National Gallery’s artist in residence. Admittedly an unusual choice, the Goldsmiths-trained artist found enlightenment in the Renaissance galleries where he became captivated by the depictions of saints. Facinated by their faith, determination and gruesome deaths, Landy has made beautifully detailed collages and engaging, spectacularly fun kinetic sculptures that animate this often reserved collection.

Had the National Gallery collection been an inspiration before the residency?

‘I’d like to say it was but it wasn’t. I didn’t come here when I was a Goldsmiths student, so it wasn’t until the residency. Suddenly I was faced with the thought of getting to know the collection and making an exhibition for 2013. But actually everyone is very relaxed; it’s a bit like Goldsmiths in some bizarre way apart from the unisex toilets. All they ever said to me was that the work has to reflect the collection. No one ever said, “You can’t do that, Landy”.’

Did you find it a challenge?

‘Well I don’t paint so I had to find my own way in. I spent my first year looking at all the paintings and I became aware of all the symbols. I like repetition, so that intrigued me, so it was St Catherine and her wheel (there are 35 depictions of the saint in the collection) and then I started to read The Golden Legend, the stories of the saints.’

How did you choose the paintings that you have brought to life in the sculptures?

‘I’m like Baron Frankenstein, digging around getting various body parts from different parts of the Renaissance. I like the idea of fragments because the works are fragments taken from something else, from altarpieces and they’re on the walls now as artworks.’

Why is viewer participationpart of your work?

‘When I was a student in 1982 I saw Jean Tinguely’s exhibition where he brought bits of junk to life and it made a real imprint on me as a young artist and somehow I wanted to duplicate that. I like the idea of people participating with the sculptures in a different way, you put your foot on the electric foot pedal that cranks up the motor that makes the wheel spin round, you don't get that in paintings. I wanted to engage the public in a different way to the way paintings engage the public.’

And where did the mechanical parts in the sculptures come from?

‘Well I wanted it to look like they’re from my childhood in the ‘70s, when you would have gone to scrap heaps and junk yards, but now you have to go to Ebay or markets as everyone knows the value these days. Junk is expensive.’

Past work has dealt with Western value systems and consumerism.

‘There are strands about value and worth, whether it’s people or objects. With the saints, I like the idea that we’ve forgotten about them and they’ve been junked, really.’

What can visitors expect all the different saints to be doing?

‘I have a St Catherine wheel, which is based on a Pinturicchio painting with the legend of St Catherine on the wheel, so members of the public can spin the wheel – it’s like a wheel of misfortune you spin to see your fate: for example, you will never find a man good enough; or you get thrown into a dungeon with scorpions. Then I have a St Francis, which is based on Sassetta’s painting, he’s without a head and a crane goes inside and pulls out T-shirts that says chastity, obedience and poverty, representing the three knots on his habit’s cord; St Jerome beats his chest; St Apollonia bashes herself in the face and pulls out her teeth; and another St Francis, this time a donation box that when you put money in, he hits himself over the head with a crucifix. There’s a lot of hitting going on.’

It’s a bit Punch and Judy.

‘Yes there’s lots of beating. I used Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano’s painting of doubting Thomas. It’s just his finger and the chest of Christ, so the finger hits his chest, it’s like a punch bag, bits fall off and fly off and they start to erode. The finger at the moment is actually making really beautiful marks on the chest but it’s also starting to make a hole where the stigmata would have been. It’s started to break down the paint, fiberglass and it’s made a hole. That’s what I got really excited about when you get things working for the first time, and they actually started to destroy themselves and that’s the element I really enjoy.’

Destroying things has been a part of your work over the years.

‘I can’t help it. I have done Acts of Kindness, but I haven’t picked the good saints, for example St Dorothy who drops flowers and apples from heaven, or St Nicholas who gives out golden balls to people. I’ve picked more kind of martyrs who mostly meet a grisly ending.’

Do you feel an affinity to any of them?

‘Chest beating I do quite often. And head banging. There’s lots of self-flagellation in art. I would normally flagellate my assistants, but I haven’t got any, so I only have myself to flagellate. Quite a lot of time I was wondering around here wondering why I agreed to do this, so there is a lot of “woe is me, I’m not worthy, I’m not good enough”, a lot of that goes on. Flagellation.’

Top art features

Discover Time Out original video