Snip, snip, snip... you can almost hear scissors slicing through paper as you look at Hannah Höch's subversive collages. Perhaps a sly giggle too, as images from newspapers and fashion magazines are chopped up and rearranged to become brilliantly bizarre hybrid figures. The only female member of the Berlin Dada movement, which rebelled against the horrors of WWI, Höch first unleashed her radical art just under a century ago and her distorted pictures mirror the fragmentary nature of a society shattered by conflict then bloated by Weimar-era excess. Her art was as sharp as her bob haircut. 'A lot of people have used collage in the past 100 years but Höch is the most important female artist to work with the medium,' says Daniel F Herrmann, curator of what - incredibly - is the first exhibition of the German artist's work in the UK.

'Her art was as sharp as her bob haircut'

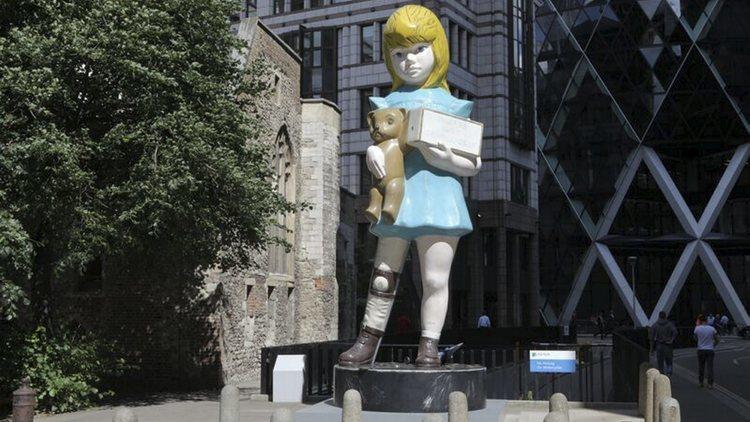

Höch's rebelliousness socks you right between the eyes in the 1930s series 'From an Ethnographic Museum', in which images of women's bodies are collaged with 'tribal' sculptures. Referring to the objectification of women, Höch was a pioneer of feminist art. Yet, according to Herrmann, 'hers is a fairly conventional story for German women at the time. The daughter of middle-class parents from a small-ish town, Gotha, Höch moved to Berlin in the 1910s, starting in a traditional way at the craft school. What's interesting is that at a very early stage she took that traditional notion of craft and turned it into something rebellious.'

A household name in Germany, Höch is barely known outside of art circles here. International art history may have labelled her in its footnotes as a Dadaist muse but, as Herrmann explains, 'she was anything but a backseat figure. She was clearly right out there with the boys and very open about doing things differently.'

Artistic daring was matched by personal courage. In the 1920s, Höch split from her lover, the Dada artist and poet Raoul Hausmann, and started a relationship with the female poet Til Brugman. Living as a couple as the Nazis came to power, they moved to the outskirts of Berlin, keeping a low profile for the duration of WWII. Höch continued to make work until her death in 1978, by which time her DIY aesthetic was readily adopted by punk. Höch still has plenty to say to today's cut-and-splicers. 'It's interesting just how many artists nowadays find her work relevant,' says Herrmann. 'What really surprises me is just how fresh every single work looks. I think visitors will love the collages for their rebellious politics and for their poignant beauty. We're really excited that we get to show her to a London audience.'

![Hannah Höch Hannah Höch ('Ohne Titel (Aus einem ethnographischen Museum) (Untitled [From an Ethnographic Museum])', 1930)](https://media.timeout.com/images/101380707/750/562/image.jpg)