The Tate Modern is one of London - and the world’s most iconic art galleries. As well as having an international collection of modern and contemporary artworks that few can beat, it is a historic piece of architecture worth visiting in its own right. It’s hard to imagine how empty London’s modern art scene must have been before this place opened, but we’re sure glad it did. Tate Modern is one of four Tate venues in the UK, and it welcomes a stonking 5 million visitors through its doors each year.

The gallery opened in 2000, making use of the old Bankside Power Station. The imposing structure on the banks of the Thames was designed after WWII by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott, the same architect behind Battersea Power Station. It was converted by Herzog & de Meuron, who returned to oversee a massive extension project. This started with the opening of the Tanks in 2012, and ended with the brand-new Switch House extension in 2016.

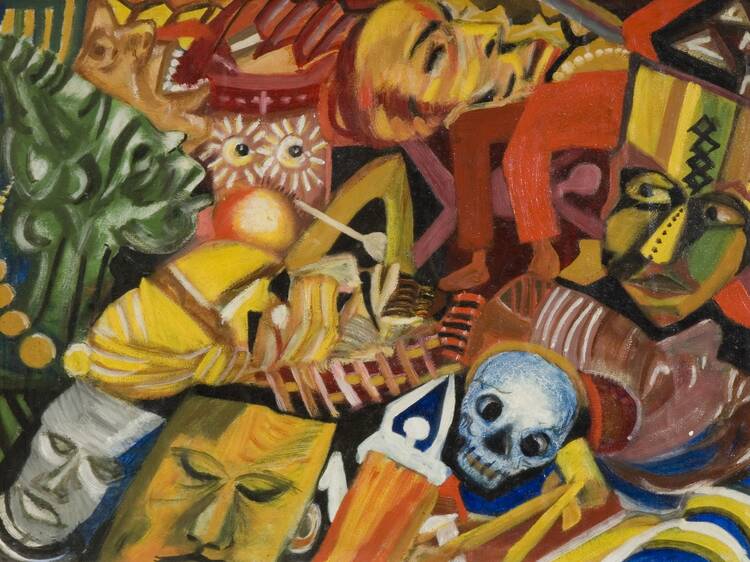

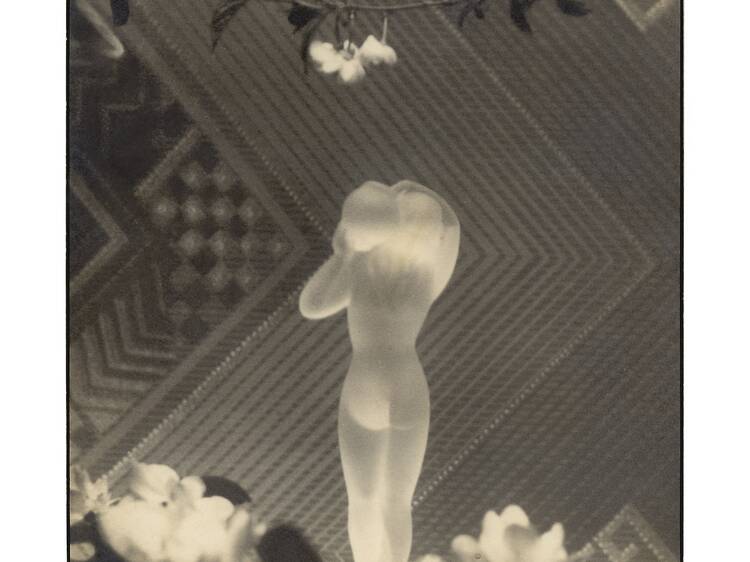

The Tate Modern's permanent collection features work by art royalty including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Barbara Hepworth.

The gallery boats some of the best contemporary art from all across the globe. With new exhibitions always on offer, you can return to gallery time and time again and expect to come across something new.

If you fancy doing something a little bit different on a Friday night, head on down to the Tate Modern on the last Friday of each month for Tate Lates. These free after-hours events blend art, music, workshops, talks and film, giving attendees the chance to interact with art in a unique and exciting way. Often themed around an exhibition currently showing in the gallery, they tend to fill up fast. So, we recommend heading down to the gallery straight after work to be sure to get in.

Monday-Sunday 10.00am-6.00pm

The main gallery is not ticketed and free to attend.

Tickets to specific exhibitions are available from the website or in person.

If you're a Tate regular, we'd recommend getting membership for £75 a year. It gives you unlimited free entry to all exhibitions across the Tate galleries, as well as access to private membership rooms, special events and a 10% discount in the shop.

Discover Time Out original video