For an artist so intimately concerned with the outward appearance and psychological contents of the human head, the strange tale of Francisco de Goya’s own bonce seems as cruelly ironic as it is grimly fascinating. The artist is buried at Royal Chapel of St Anthony of La Florida in Madrid, except only his body rests there: his skull has never been found. Born near Zaragoza, Spain, in 1746, Goya died in self-imposed exile in Bordeaux in 1828. When his body was exhumed for repatriation decades later, it was headless. Rumours abound: that it was kept by a phrenologist with the artist’s consent; that he requested for it to be buried alongside the body of the Duchess of Alba (see right); even that it languished in an artist’s studio for years, only to be blown up by a medical student who filled it with fermenting chickpeas. Such stories add to the mythology that surrounds an artist who, more than any other of the early nineteenth century, taps into the joy, mystery, folly and futility of life, as witnessed in his harrowing 'Disasters of War' series and 'Black Paintings', which he made for his home, Quinta del Sordo (Deaf Man's Villa), on the outskirts of Madrid between 1819 and 1823.

It’s often said that Goya is the last of the Old Masters and first of the moderns. Certainly he straddles not just centuries but epochs – the Ancien Régime, the birth of the Enlightenment, the savage Napoleonic invasion of Spain and eventual restoration of a reactionary monarchy. These turbulent episodes are equalled by seismic events in Goya’s own life, notably the nervous illness that, in 1793, left him deaf.

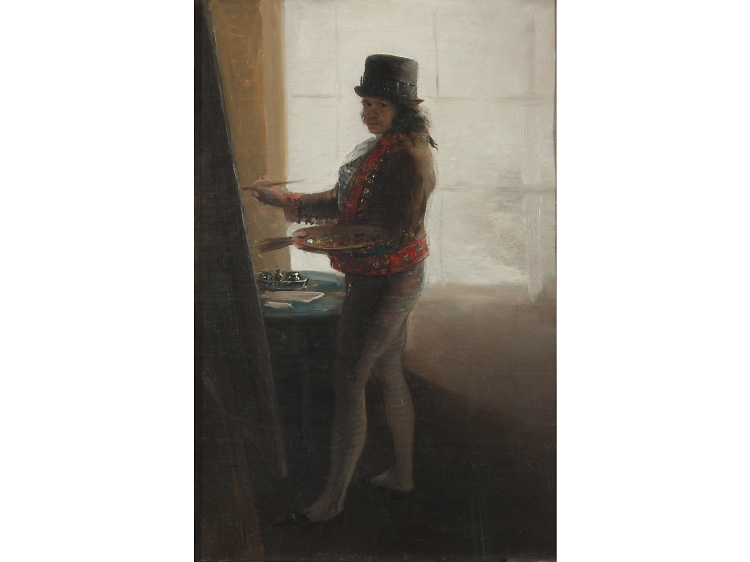

The National Gallery’s show is the first full-scale survey to focus on Goya’s portraits and it chronicles the key players of the times – royals, despots, politicians, musicians, thinkers. Goya took time to get really good. He failed to get into the Royal Academy in Madrid twice and was 37 before he received his first important portrait commission. He loved money and was obsessed with status, particularly his own, and eventually became painter to three kings. Which doesn’t equate with the kind of flattery you might expect from a portrait painter for hire. Whether he’s painting a prince or a prostitute, Goya can’t conceal that he’s looking with love, admiration, or contempt. He’s credited with being the father of the ‘psychological portrait’, but the chance to get inside Goya’s own head is the biggest thrill of the show. Self-portraits from his career will be hung throughout the galleries, so you’ll get to see the artist looking not just at those around him but also at himself, in times of happiness, sadness and madness. Here are some of the key works on show.