The Maddox-Wilson family are already pretty deranged, even by the usual standards of aristocratic eccentricity. But things start to degenerate further when an unnamed stranger appears in their dilapidated country mansion – unnamed, because they each perceive the stranger to be a different object. Soon, he begins eating his way through the books in the library – in the process somehow destabilising the family’s very ability with language – and regurgitating the masticated matter into strange, fecaloid forms.

Such is the basic plot of episodes one, two and four (there’s no three as yet) of Nathaniel Mellors’s absurdist drama ‘Ourhouse’, a sort of cross between Pasolini, Beckett and Monty Python – not that plot is necessarily the strong suit of these liltingly non-linear films. Rather, what sticks in the mind are specific scenes, frequently comical, but more often darkly demented: Daddy’s delirious, working-class impersonations, for instance, or the bizarre, bullying language-tests that his wife, Babydoll, inflicts on the Irish handyman, or his simpleton sons, debating the authenticity of prehistoric ‘pornology’.

Malapropisms, slippages and misspellings abound, creating the continual feeling – sometimes slightly belaboured – of teetering on the brink of nonsense, of things slipping towards meaninglessness. Yet there’s also the reciprocal sensation: an eerie, esoteric, paranoid awareness that anything, therefore, is potentially brimming with hidden meaning.

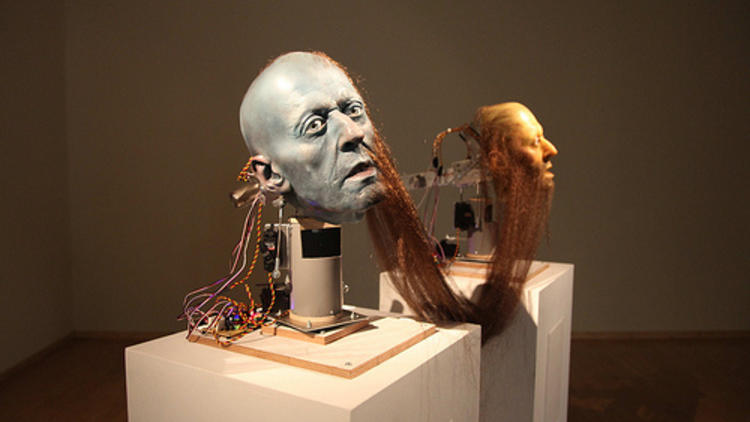

The exhibition ends with one of the animatronic, prosthetic-face sculptures that are becoming a sort of trademark for Mellors: two identical casts of the Daddy character from the films – though one an abnormal, hideous blue colour – connected by an umbilical loop of beard hair, and spouting manic, fragmented phrases. And yet, for all their juddering movements and cyclical utterances, these android objects lack the more palpable horror and humour of the films themselves – that urgent, all-too-human sense of desperately groping towards linguistic coherency.