Conflict has an immeasurable impact on civilisations, landscapes, countries, cities, towns, loved ones and our memories. So a photographic exhibition about war might not strike you as an engagingly rewarding blockbuster show. But this enlightening and thoughtful survey is exactly that. Through images taken moments, days, weeks, months and years after the event, the effect and trauma of war is re-evaluated from the reflective viewpoint of artists and photojournalists without relying on explicit imagery.

In the first gallery, four grainy black-and-white photographic prints of pillowy cloud formations are displayed opposite a peaceful landscape devoid of activity, but for a few puffs of grey smoke. If you didn’t read the wall text, you’d be unaware of the importance of these seemingly incidental moments. The fluffy mass is in fact the mushroom cloud from the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the photo was taken by Toshio Fukada some twenty minutes after the event. Similarly the dusty vista by Luc Delahaye captures the moment after intensive bombing by the US of the Taliban in Afghanistan. These images are an abstract way to open a show about war, and successfully set it up to build a lasting impression.

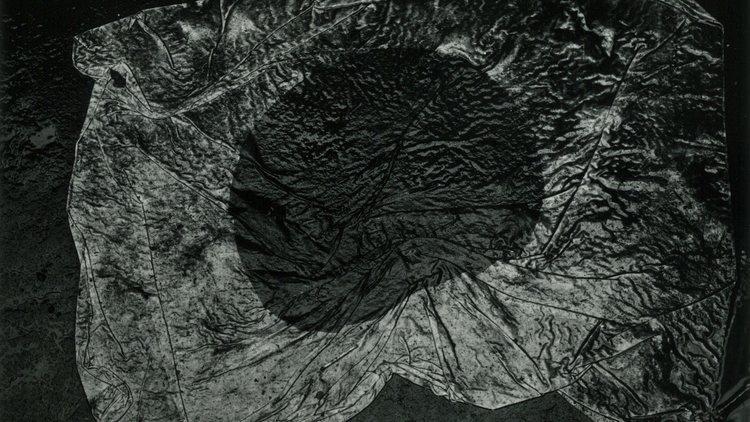

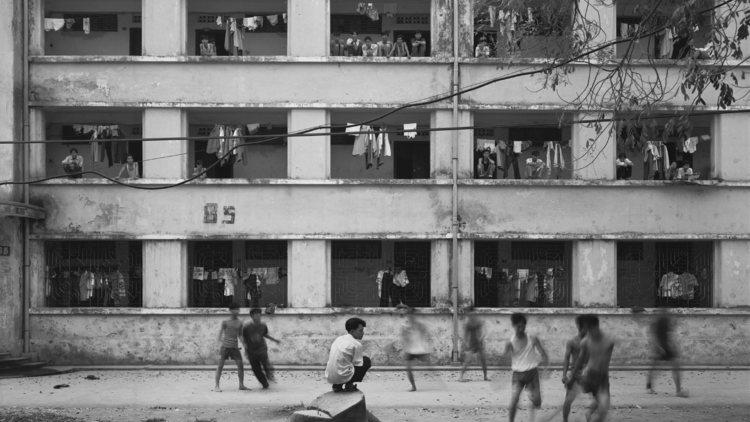

There are haunting works such as Don McCullin’s photograph of a shell-shocked Marine taken post-combat in Vietnam. Clenching his rifle, he seems to stare right through you in an utterly distressed trance. Extraordinary pieces include Matsumoto Eiichi’s photograph in which the silhouette of a guard has been etched onto the side of a building, a result of the Nagasaki atomic explosion three weeks earlier. There are surprising exhibits like postcards of battlefields, produced for the glut of post-World War I tourists on ‘pilgrimages’ to see the battlefields and destruction first-hand. The ruins of war reverberate throughout the entire show, from Pierre Antony-Thouret’s images of Reims, a city reduced to rubble, to Simon Norfolk’s series ‘Afghanistan: Chronotopia’, 2001-02 which focuses on towns scarred by ongoing warfare.

Other artists have sought to reconnect the human, individual aspect often lost in the reporting of unimaginable genocides the world over. Diana Matar’s ‘Evidence’ series gives a voice to the victims who died under Gaddafi’s regime in Libya. Rather bleak, unpopulated locations are paired with harrowing facts about human-rights atrocities. Taryn Simon’s documentation of the 1995 Srebrencia massacre charts the effect on a family’s bloodline through portraits of surviving members and images of personal possessions recovered from mass graves.

Unfortunately there just isn’t enough space in this review to cover all the phenomenal projects included in this mammoth exhibition – although the Archive of Modern Conflict’s display of idiosyncratic war-related paraphernalia merits a mention.

You will feel educated and heart-broken in equal measure by these awe-inspiring photographs that challenge the way war can be portrayed, and the way we engage with photographs so that we actually see the inconceivable.

Freire Barnes