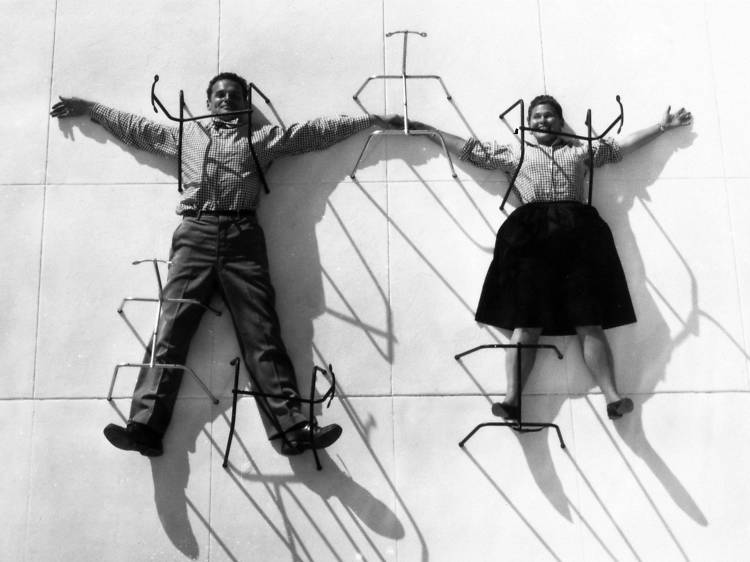

1. They were the first design power couple

‘Charles used to say: “Ray, my wife not my brother,” because people made that mistake endlessly,’ says Ince. The mistake is perpetuated to this day. In fact Ray (born Bernice Alexandra Kaiser in 1912) met her future husband Charles at college in Michigan in 1940. Ray was a student, Charles was a teacher (and – scandal – married to someone else). They began working together soon after and, after Charles was divorced, moved to California, where they eventually set up the Eames Office. As much as it follows their design evolution, the show is a story of their love affair, filled with snapshots, mementos and notes to each other. ‘Anything I can do, Ray can do better,’ Charles was fond of saying. Charles died in 1978 and Ray died on exactly the same day ten years later. ‘She kept asking what day it was, which is rather beautiful,’ says Ince.